Sometimes the sugar isn’t that sweet. Sometimes it’s really fatal. Saccharification occurs when excess sugar, called reducing sugar, adheres to important proteins in the body. This process is associated with diabetes and obesity. It is usually something to avoid, and the body relies on FN3K kinases to destroy glycation. But cancer turns everything into your mind.

In certain types of cancer, glycation prevents tumors from utilizing proteins that help the tumor grow and expand. In such cases, Professor Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) and HHMI Investigator Leemor Joshua-Tor He says he doesn’t want to get fn3k involved. She explains:

“Tumors require a large amount of sugar to grow. So sugar is attached naturally to this protein and attenuates it. It’s like stuffing something into the mouth. Tumors cannot grow and grow.”

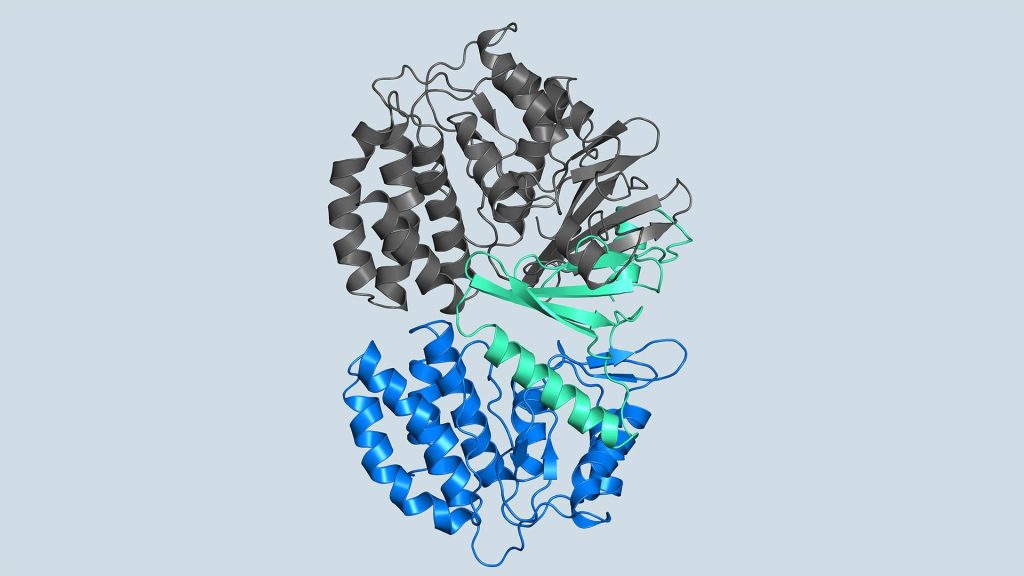

The role of FN3K in decomposing glycation has been known for decades. However, the structure of kinases required for drug development has remained a mystery until now. Joshua-Tor, CSHL Postdoc Ancourghgand their team revealed the 3D structure of human FN3K captured in various states for the first time. These structures can point to the path to new cancer therapy and provide hope for patients suffering from fatal illnesses.

“Kinases are common in our cells,” says Joshua Toll. “So, in order to target only FN3K, rather than the other kinases we need, we need to know exactly what it looks like. This gives us an accurate model.”

This model allowed the team to lay out the entire process by which FN3K decomposes glycation. They discovered that unlike most kinases, human FN3K contains an amino acid called tryptophan. Yes, it’s the same tryptophan that knocks you out after a big meal. When the team removed it from FN3K, the kinase became inactive. And when they changed it to another amino acid, it converted FN3K to a “super enzyme,” says Garg.

“Control one small amino acid allows you to control the entire enzyme,” he explains. “This is important for designing specific drugs and targeting FN3K alone.”

Collaborators at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center now do just that with the new structure of the lab. Future clinical applications are still far apart. However, Joshua-Tor says the first step is to identify existing small molecules that bind to FN3K.

“When you think about it, it’s really amazing,” she says. “These enzymes are so tweaked that everything has to be in the right state at the right time. It would be great if we could exploit it with an early drug or molecule and move on from there.”

It was written: Nick Worm, Communication Specialist | [email protected] | 516-367-5940

Funds

Starr Foundation, National Institutes of Health, Howard Hughes Medical Research Institute

Quote

Garg, A. , et al. , “Molecular basis of human FN3K-mediated phosphorylation of glycate substrates,” Natural CommunicationJanuary 22, 2025. doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-56207-z