Image source, MRC Institute of Medical Research/Duke University

A drug has extended the lifespan of lab animals by nearly 25 percent, and scientists hope the discovery could also slow ageing in humans.

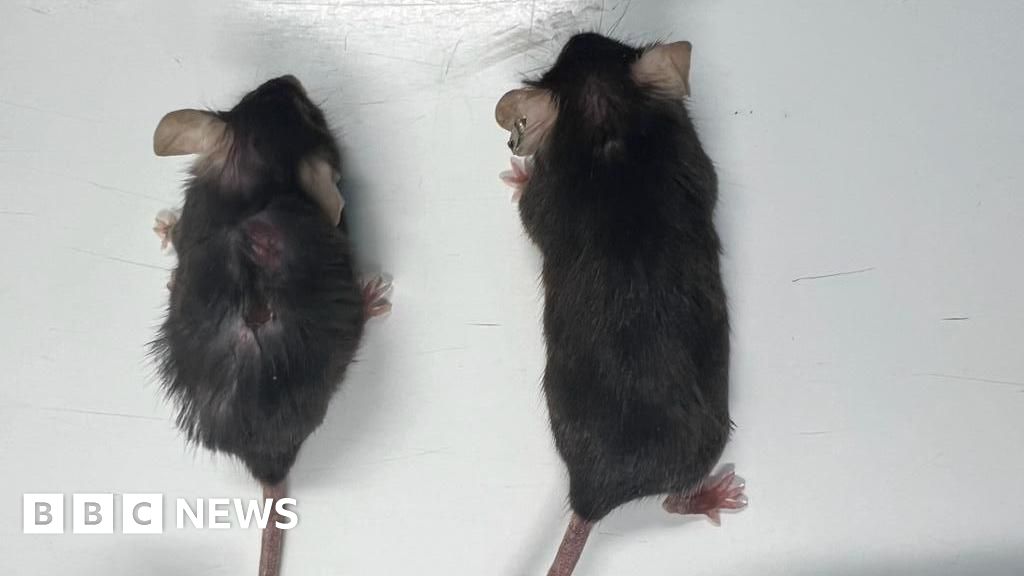

The treated mice were known in the lab as “supermodel grannies” because of their youthful appearance.

They were healthier, stronger, and less susceptible to cancer than their non-medicated peers.

The drug has already been tested in humans, but it’s unclear whether it will have the same anti-ageing effects.

- author, James Gallagher

- role, Health Science Correspondent

- twitter,

-

The quest for longer life spans is woven throughout human history.

But scientists have long known that the ageing process is flexible: lab animals can live longer if they are forced to eat drastically less.

The field of aging research is currently booming as researchers seek to uncover and manipulate the molecular processes of aging.

The team, from the MRC Institute of Medical Sciences, Imperial College London and Duke-NUS Medical School in Singapore, were investigating a protein called interleukin-11.

Its levels in the body increase with age, contributing to elevated levels of inflammation and flipping several biological switches that control the pace of aging, the researchers say.

A longer, healthier life

The researchers conducted two experiments.

- First mice genetically engineered to be unable to produce interleukin-11

- In the second study, mice were allowed to reach an age of 75 weeks (roughly the equivalent of 55 years in humans) and then given regular doses of a drug that flushes interleukin-11 from their bodies.

Old laboratory mice often die from cancer, but those lacking interleukin-11 developed much lower levels of the disease.

They had improved muscle function, lost weight, had healthier coats and scored better in many measures of frailty.

I asked one of the researchers, Professor Stuart Cook, whether the data was incredible.

He told me, “I’m trying not to get too excited about it for the reasons you mention. I think it might be too good to be true.”

“There are a lot of questionable drugs out there, so I try to stick to the data. Data is the most powerful thing.”

He believes the treatment is “definitely” worth trying on human ageing, claims it would be “a game changer” if it were successful, and said he would be open to trying it himself.

But what about humans?

The big unanswered questions are whether the same effects will be achieved in humans and whether the side effects are tolerable.

Interleukin-11 plays a role in the early development of the human body.

In rare cases, people are born without teeth. This can change the way the bones in the skull fuse, affect joints and require corrective surgery, as well as alter how the teeth grow in. It can also affect scarring.

Researchers believe that later in life, interleukin-11 plays a negative role in promoting aging.

The drug, an artificial antibody that attacks interleukin-11, is being tested in patients with pulmonary fibrosis, a disease that causes scarring in the lungs and makes it difficult to breathe.

Prof Cook said that although the trials were not yet completed, the data suggested the drug was safe to take.

This is just the latest approach to using drugs to “treat” ageing: metformin, a drug used to treat type 2 diabetes, and rapamycin, a drug taken to prevent rejection of organ transplants, are both being actively studied for their anti-ageing properties.

Prof Cook believes that medicines may be easier for people to follow than calorie restriction.

“Do I want to live a life of half-starvation and utter discomfort from the age of 40 onwards, when I only have five more years to live? I don’t think so,” he said.

Image source, Duke-NUS Medical School

Professor Anissa Wijaya, from Duke-NUS’s School of Medicine, said: “Although our study was carried out in mice, studies in human cells and tissues have confirmed similar effects, so we are hopeful that these findings will be highly relevant to human health.”

“This study is an important step towards a deeper understanding of aging and demonstrates a potential treatment to extend healthy aging in mice.”

“Overall, the data seems solid – this is a new treatment that targets mechanisms of ageing and may help to improve frailty,” said Ilaria Bellantuono, professor of musculoskeletal ageing at the University of Sheffield.

But problems remain, including a lack of evidence for patients and the cost of producing such a drug, and “it’s unthinkable to treat every 50-year-old for the rest of their lives,” he said.