Recent research published in the journal Translational Psychiatry It turns out that a single dose of a common antidepressant, specifically a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, can change the way the brain processes internal sensations. This effect is particularly pronounced when a person is feeling anxious, suggesting a subtle interplay between serotonin, interoception (your sense of internal states), and anxiety.

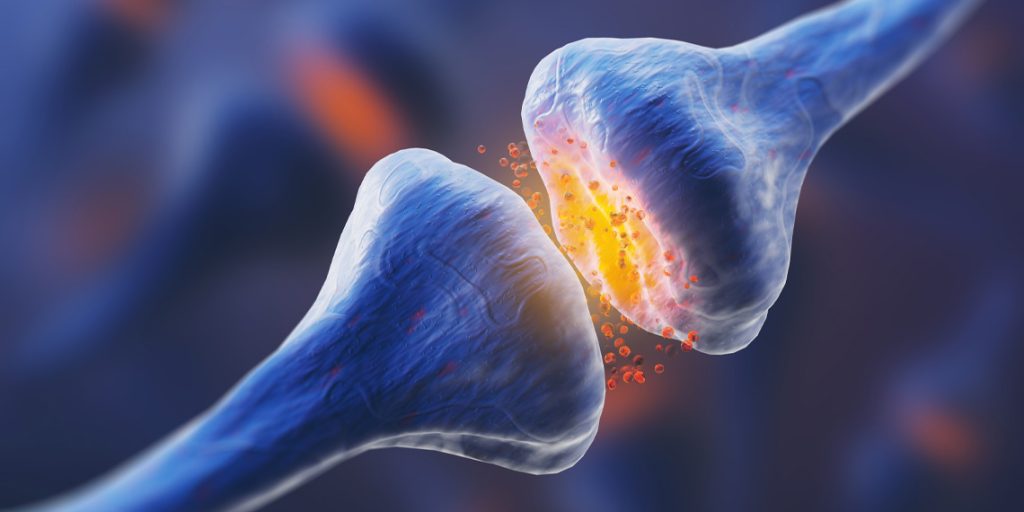

The researchers aimed to understand how serotonin, a key neurotransmitter in the brain, affects interoception. While serotonin’s role in regulating sensory processing such as vision and hearing is well established, its effect on interoception, particularly with regard to normal internal sensations such as heart rate and stomach activity, was unclear.

“We know very little about how the brain controls sensory information coming from within the body. Similarly, we didn’t know why serotonergic antidepressants change our mood, even though millions of people take them daily,” said study author Dan Campbell Meiklejohn, PhD, PhD, professor of neuroscience and neuroscience at the University of California, San Diego.Dr. Daniel CM), Senior Lecturer at the University of Sussex.

“Serotonin and interoception have each been independently associated with the same psychiatric disorders, brain activation and behaviors, so testing whether serotonin influences interoception seemed like a good starting point to bridge the gap between these two stories.”

The study involved 31 healthy participants aged between 18 and 35 years. The participants underwent a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized crossover experiment. Each participant was tested twice, once after a single dose of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram (20 mg) and once after a placebo. There was an interval of at least one week between sessions.

Participants performed a visceral interoception (VIA) task in which they focused on sensations from their heart and stomach while their brain activity was monitored using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). The task also included a control condition in which participants focused on visual stimuli. This design allowed the researchers to isolate the brain’s response to interoceptive sensations and compare it to exteroceptive (external sensory) processing.

Results showed that a single dose of citalopram significantly reduced neural responses to interoceptive sensations. Researchers found that increased serotonin levels reduced neural activity in the amygdala and posterior insular cortex, areas important for processing sensory and emotional information.

“The reduced neural response suggests that serotonin has a moderating effect on the brain’s processing of internal sensations. This finding is notable because it extends the known effects of serotonin from exteroceptive sensory processing, such as vision and hearing, to interoceptive sensory processing.”

What’s interesting about this study is that the effects of serotonin are state-dependent. The researchers found that the relationship between anxiety and interoception was modified by citalopram. Under placebo, higher anxiety levels were associated with greater neural activity in the anterior insula and orbitofrontal cortex during the heart-focused task.

However, when subjects were given citalopram, this relationship significantly flattened out, suggesting that serotonin not only regulates interoception, but does so in a way that is influenced by an individual’s anxiety levels.

“The findings suggest that serotonin changes the way the brain processes sensations from the body when you’re anxious, including changes in the way your heart processes sensations,” Campbell Meiklejohn told PsyPost.

The researchers also found that citalopram’s effect on the processing of stomach sensations was a strong predictor of change in anxiety: Participants who experienced a greater reduction in neural response to stomach sensations also saw changes in their anxiety levels.

“We were surprised to find that the effect of SSRIs on sensory processing in the stomach was the best predictor of the effect of SSRIs on anxiety (which may be more or less in different people in the short term),” Campbell-Meiklejohn says. “This is a preliminary finding, but it shows that ‘gut feelings’ are not just an expression.”

However, this study only looked at the effects of a single dose of citalopram, whereas real-world treatment involves long-term use. This raises questions about the long-term effects of serotonin modulation on interoception. Future studies could explore the chronic effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and include a more diverse group of participants.

“The effects of a single dose in healthy volunteers are not necessarily predictive of what will happen in patients who have been taking it for weeks,” Campbell-Meiklejohn said. “Without further research, we cannot speculate on what this means for patients on SSRI treatment.”

Investigating how these findings apply to patients with anxiety disorders and testing other antidepressants may provide greater insight into the mechanisms and therapeutic potential of serotonin regulation in the treatment of psychiatric disorders.

“We want to know whether serotonin’s effects on interoception are a mechanism for the therapeutic effect of SSRIs on anxiety, and whether it could explain other effects of serotonin transmission, such as on impulsivity and aggression,” Campbell-Meiklejohn explained.

the study, “General and anxiety-related effects of acute serotonin reuptake inhibition on neural responses related to visceral sensation” was written by James J. A. Livermore, Lina I. Skora, Kristian Adamatzky, Sarah N. Garfinkel, Hugo D. Critchley, and Daniel Campbell-Meiklejohn.