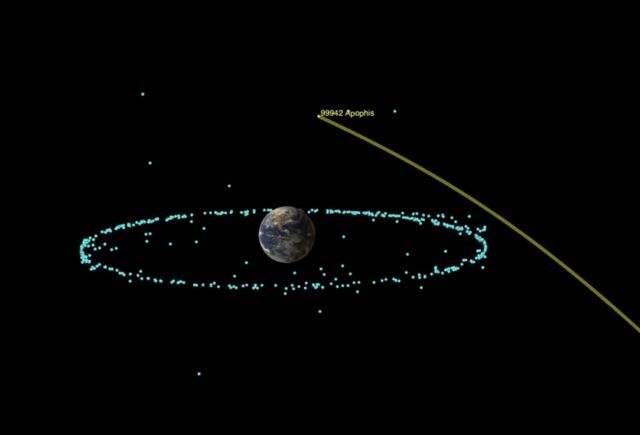

For nearly two decades, scientists have known that an asteroid named Apophis will make an unusually close approach to Earth on Friday, April 13, 2029. But most officials at the world’s space agencies are paying less attention after recent measurements ruled out Apophis being close to hitting Earth anytime soon.

Now Apophis is back on the table, but this time as a scientific opportunity, not a threat. The problem is that there isn’t much time to design, build, and launch a spacecraft that can land near Apophis within the next five years. Luckily, there are designs, and in some cases existing spacecraft, that governments can repurpose for missions to Apophis, a rocky asteroid about the size of three football fields.

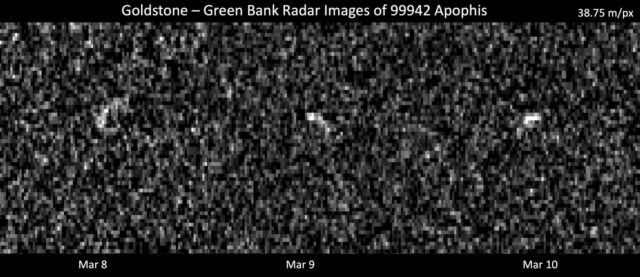

Scientists discovered Apophis in 2004, and initial measurements of its orbit indicated there was a small chance it could collide with Earth in 2029 or 2036. In 2021, scientists used more detailed radar observations of Apophis to determine that it poses no danger to Earth for at least the next 100 years.

“The three most important things about Apophis are that it misses Earth. It misses Earth. It misses Earth,” said Richard Binzel, a professor of planetary science at MIT, who has co-hosted several conferences since 2020 aimed at rallying support for a space mission to capitalize on Apophis’ 2029 opportunity.

“An asteroid this large comes this close once every 1,000 years, if not more,” Binzel told Ars. “This is an experiment that nature is doing for us. When we bring an asteroid this large close, the Earth’s gravity and tidal forces will tug on it and possibly shake it up. How the asteroid responds will give us great clues about its interior.”

Binzel says it’s important to catch a glimpse of Apophis before and after its closest approach in 2029, when it will pass within 20,000 miles (32,000 kilometers) of Earth’s surface — closer than the orbit of a geostationary satellite.

“This is a natural experiment that will tell us how hazardous asteroids form, and there’s no way to get this information without very complex spacecraft experiments,” Binzel said. “So this is a once-in-thousands-years experiment that nature is running for us, and we have to figure out how to observe it.”

This week, European Space Agency announces preliminary approval The mission, called RAMSES, is scheduled to launch in April 2028, one year before the Apophis flyby, and rendezvous with the asteroid in early 2029. If ESA member states give full approval to the development next year, the RAMSES spacecraft will accompany Apophis throughout its Earth flyby, collecting images and other scientific measurements before, during and after its closest approach.

The challenge of building and launching RAMSES in under four years will be a good rehearsal for a possible future real-world scenario. If astronomers discovered an asteroid on a collision course with Earth, a quick response might be needed. With enough time, space agencies could launch a reconnaissance mission and, if necessary, perhaps a mission to detect the asteroid. This will be demonstrated on NASA’s DART mission in 2022..

“Ramses will demonstrate that humanity can deploy a reconnaissance mission to rendezvous with an approaching asteroid in just a few years,” said ESA’s Planetary Defence Director Richard Moisle. “This type of mission will be the linchpin of humanity’s response to hazardous asteroids. The reconnaissance mission will first be launched to analyse the trajectory and structure of the approaching asteroid. The results will be used to determine how best to redirect the asteroid, or to rule out possibilities of avoiding a collision, before expensive deflection missions are developed.”

Brush off the cobwebs

To make the RAMSES launch possible in 2028, ESA will need to build about half a tonne of A spaceship called Herais due to launch in October on a mission to investigate the binary asteroid system that will be the target of the DART impact experiment planned for 2022. ESA officials say mimicking Hera’s design will reduce the time needed to get Ramses to the launch pad.

“Hera demonstrated that ESA and European industry can meet tight deadlines, and RAMSES will follow that example,” said Paolo Martino, ESA’s head of development of RAMSES, an acronym for Rapid Apophis Mission for Space Safety.

ESA’s Space Safety Committee recently approved preparatory work for the RAMSES mission, using funds already in the agency’s budget. German spacecraft manufacturer OHB, which produces Hera, will also lead the industrial team working on RAMSES. The cost of RAMSES will be “significantly lower” than the Hera mission’s €300 million ($380 million), Martino said in an email to Ars.

“There’s still a lot we don’t know about asteroids, and until now we’ve had to travel deep into the solar system to study them, conduct experiments ourselves, and interact with their surfaces,” said Patrick Michel, a planetary scientist at the French National Center for Scientific Research and principal investigator of the Hera mission.

“For the first time, nature is bringing it to us and conducting the experiment itself,” Michel said in a press release. “All we have to do is watch as Apophis is stretched and compressed by strong tidal forces, causing landslides and other disruptions and revealing new material from beneath the surface.”

If final approval is granted next year, RAMSES NASA’s OSIRIS-APEX mission For Apophis, NASA is steering a spacecraft already in space, used for the OSIRIS-REx asteroid sample return mission, to rendezvous with Apophis in 2029, but it won’t reach its new target until a few weeks after its close approach to Earth. Complexities in orbital mechanics mean it can’t rendezvous with Apophis any sooner than that.

Observations from the OSIRIS Apex spacecraft, a larger probe with a suite of advanced instruments, “will give us a detailed picture of what Apophis was like after the collision,” Binzel said. “But until we know what Apophis was like before the collision, we only have one side of the picture.”

Scientists also want NASA to consider launching two stored scientific probes on an orbit that will pass Apophis before it hits Earth in April 2029. Two spacecraft built for NASA’s Janus programThe mission was canceled by NASA last year after falling victim to delays to the launch of NASA’s larger asteroid probe, Psyche. The Janus probe was scheduled to launch on the same rocket as Psyche, but problems with that mission delayed the launch by more than a year.

Despite the delay, Psyche may still be able to reach her destination. But the new launch trajectory won’t allow Janus to visit the two binary asteroids that scientists originally wanted the probe to explore. After spending about $50 million on the mission, NASA put the twin Janus spacecraft, each about the size of a suitcase, into long-term storage.

At the most recent Apophis mission workshop in April, scientists heard presentations on more than 20 concepts for measuring spacecraft and instruments on Apophis.

Among them is an idea from Jeff Bezos’ space company Blue Origin, which would use its Blue Ring space tug as a host platform for multiple instruments and landers that could descend on Apophis’ surface, assuming that research institutions have enough time and funding to develop the payloads. A startup called Exploration Laboratories has proposed partnering with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory to fly small spacecraft missions to Apophis.

“My job was to come to some kind of agreement at the end of the workshop, because if there wasn’t some agreement on the top priorities, we might not get anything done,” Binzel said. “The agreed recommendation to ESA was to move RAMSES forward.”

Workshop participants also gently urged NASA to use the Janus probe for a mission to Apophis. “Apophis is a mission to find a spacecraft, and Janus is a spacecraft to find a mission,” Binzel said. “Efficiency and basic logic dictate that a mission from Janus to Apophis be the top priority.”

Money issues

But NASA’s science budget, especially its planetary science vision, is under pressure. Earlier this week, NASA canceled plans for a lunar rover called VIPER that had already been built. After spending $450 million on the mission, it was automatically considered for cancellation because it had exceeded its original development costs by more than 30 percent.

NASA’s Science Mission Directorate’s budget this year is about $500 million less than last year’s budget and $900 million less than the White House’s budget request for fiscal year 2024. Because of the tight budget, NASA officials say they are focusing for now on completing projects already underway, such as the upcoming project, and not starting development of any new planetary science missions. Europa Clipper Mission, Dragonfly quadcopter visits Saturn’s moon Titanand the Near-Earth Object (NEO) Surveyor telescope to search for potentially hazardous asteroids.

Dan Seales, Janus principal investigator at the University of Colorado, said NASA has asked the Janus team to explore launching it on the same rocket as NEO Surveyor in 2027, which could allow Janus to capture the first close-up images of Apophis before Ramses and Osiris Apex arrive.

“This is something that we’re currently presenting in discussions with NASA to help them understand what the possibilities are,” Sears said last week at a meeting of the Small Body Advisory Group, which represents the asteroid science community.

“These spacecraft are capable of conducting future scientific flyby missions to near-Earth asteroids,” Shears said. “Each spacecraft is equipped with high-quality marine visible imagers and thermal infrared imagers. Each spacecraft has the capability to track and image asteroid systems through close, high-speed flybys.”

“The science yield from Janus’ flyby of Apophis could be one of the best ever,” said Daniela DellaGiustina, principal scientist for the OSIRIS-APEX mission at the University of Arizona.

Binzel, who has been directing the Apophis mission, said having the spacecraft escort the asteroid so close to Earth also has symbolic value: At its closest approach, Apophis will be visible over Europe and Africa.

“Two billion people are going to look at this and ask, ‘What is our space agency doing?’ And if the answer is, ‘Yes, we’re there. We’re getting there,’ meaning OSIRIS-APEX, I don’t think that’s a very satisfactory answer,” Binzel said.

“As an international space community, we hope to show on April 13, 2029 that we are there and we are watching. We are watching because we want to gain as much knowledge and understanding as possible about these objects, because one day it may be important,” Binzel said. “One day, our detailed knowledge of hazardous asteroids will be one of the most important knowledge bases for the future of humanity.”