His debut album, The Button-Down Mind of Bob Newhart, spent 14 weeks at No. 1 on the Billboard charts in 1960, beating out pop and rock records by Frank Sinatra and Elvis Presley. It was the first comedy album to sell more than one million copies, and Newhart is the only comedian to ever win Grammy Awards for Best New Artist and Album of the Year.

He didn’t emerge from the traditional nightclub arena, but rather gained popularity through his recordings – in fact, his first nightclub performance was when he recorded “The Button-Down Mind,” a song that went on to sell over 100 million copies.

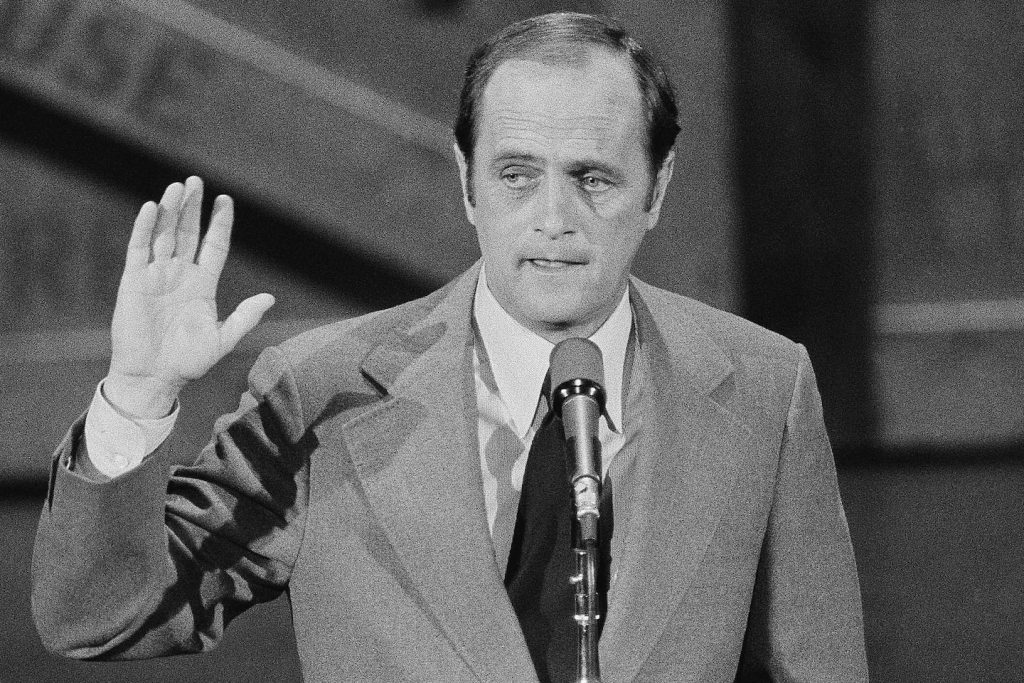

Mr. Newhart’s best-selling records helped him become one of the first comedians to win fans on college campuses: In his suit and tie and reserved manner, he looked like a young executive strolling down a hallway from a business meeting, talking about a world that was spinning off its axis.

“Comedy is a way of bringing logic to the many illogical situations of everyday life,” Newhart wrote in his 2006 memoir, “I Shouldn’t Even Do This!” “I’ve always likened what I do to a man who is convinced he’s the last sane person on Earth.”

His deadpan, foul-mouthed, “clean” approach set him apart from the confrontational, political, over-caffeinated trend of comedians of the time, including Lenny Bruce. Mort Sahl and Don Rickles He became Mr. Newhart’s closest friend.

Newhart’s suave, “button-down” style relied heavily on monotone speech and carefully placed pauses and stammers. He often introduced his sketches as observations on the business world, workplace mores, and the frustrations of everyday life.

“This comedy was intelligent,” comedian Tommy Smothers told the Chicago Tribune. 2002The year Newhart received the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor at the Kennedy Center. “Bob had a great sense of space, a sense of timing that is so essential to comedy. He never told an over-the-top joke. It was all about the attitude and intonation and the space you had to space the words. That was his great gift.”

By looking at familiar situations from fresh angles, Newhart discovered his own style of humor. He played a driving instructor with clueless students, the beleaguered captain of the nuclear submarine Codfish with a mutinous crew, and a bus driving instructor teaching his students the correct way to leave passengers on the road. “What you want to do is just ease up, keep holding onto hope that you’re going to catch up with the bus, you know? … Did you see when he slammed the door in her face? That’s what we call the perfect pull-out.”

One of Newhart’s major contributions to comedy was performing what was essentially a “straight man” routine, in which the audience only heard one side of an increasingly urgent conversation in the form of a telephone conversation.

“Listen, Abe,” he imagined a publicist saying to President Abraham Lincoln, “What’s the problem? You’re thinking about shaving it? Well, Abe, don’t you understand that that’s part of the image?”

One of Newhart’s most popular skits was based on the idea of introducing a new product with no clear market niche, in which Newhart imagined a call by Sir Walter Raleigh to the East India Company’s London headquarters to report on a new purchase in the American colonies.

“What tobacco, Walt?… Just to be clear, Walt, you bought 80 tons of leaf? Walt, this might be a bit of a surprise to you, but here in England, when autumn arrives, it’s about time for… that’s not that kind of leaf, is it?”

Another routine was built with a workplace emergency in mind that wasn’t covered in employee orientation — in this case, on a security guard’s first night working at the Empire State Building, he’s not sure what to do when King Kong starts climbing the outside of the building.

“Something’s happened, Captain,” the guard hesitantly tells his boss on the phone. “It’s not in the guard manual. I looked it up in the index, yes, Captain. I looked it up for unauthorized personnel, unauthorized pass holders, monkeys, monkey toes. Monkeys, monkey toes, yes, Captain… You see, this is no ordinary monkey, Captain. It’s between 18 and 19 stories tall, depending on whether there’s a thirteenth floor or not.”

After years as a stand-up comedian and frequent appearances on television variety shows, Newhart realized that his unassuming stage persona of a slightly bewildered everyman would translate well to television situation comedies.

“The Bob Newhart Show,” which aired on CBS from 1972 to 1978, was part of the network’s powerful Saturday comedy lineup, along with “The Mary Tyler Moore Show,” “All in the Family” and “The Carol Burnett Show.” Mr. Newhart played a Chicago psychologist who addressed the funny foibles of his clients.

His wife was played on the show by the raspy-voiced actress Suzanne Pleshette, and Mr. Newhart maintained that the couple had no children.

“I didn’t want to do another show with a dopey dad who always gets into trouble and precocious kids and a mom who rescues them,” he told the Newark Star-Ledger in 2001. “That was one of the few things I insisted on, and I think that was one of the reasons the show was successful.”

“Newhart,” which aired on CBS from 1982 to 1990, starred him as a guidebook author turned Vermont innkeeper who dealt with quirky locals, with a finale that became one of the most memorable in TV history.

Newhart, who was hit by a golf ball and knocked unconscious, woke up in bed next to Pleshette in a Chicago bedroom last seen on “The Bob Newhart Show” 12 years ago.

“Hey, wake up,” Newhart says, “I can’t believe the dream I just had.”

“OK, Bob,” Pleshette said, and the audience erupted in astonishment and applause. “What’s going on?”

“I was running an inn in this weird little town in Vermont,” Newhart explains.

“I’ve never played in a nightclub.”

George Robert Newhart was born in Oak Park, Illinois, on September 5, 1929, and grew up near Chicago, where his father ran a plumbing and heating business.

Mr. Newhart graduated from Loyola University Chicago in 1952, then served two years in the Army. He enrolled in law school but dropped out, partly because he spent his nights doing amateur theater and early comedy endeavors. He worked in accounting and advertising, and also worked for the Illinois Unemployment Insurance Agency.

“I was getting paid $60 a week, but the people I was giving money to were only getting $55 a week,” he later said, “and they only had to come into the office once a week.”

He admired the dry, understated comedy of such early stars as Jack Benny, Fred Allen, and the team of Bob and Ray.Bob Elliott While working in an office, Newhart improvised comedic telephone conversations with his friend Ed Gallagher, and then began writing and recording formal comedy skits.

Some of the songs were played on Chicago radio, and Newhart continued as a solo performer after Gallagher moved away. Shelley Berman Though Newhart later accused him of stealing his line, the call has been a comedy staple since the days of Alexander Graham Bell.

Although Mr. Newhart made brief appearances on morning television shows, he was still living with his parents and working a series of middling jobs when a Chicago radio DJ recommended him to Warner Bros. Records.

The label wanted to sign him to a deal and record his nightclub performances.

“And I said, ‘Well, that’s going to be a problem,'” Newhart told NPR in 2006. “Because I’d never played a nightclub.”

His first show, at a Houston club, was called “Bob Newhart’s Button-Down Mind,” a title that was a satire of Mr. Newhart’s clean-cut, businesslike image.

The album’s unexpected success made Newhart a star, leading to appearances on television variety shows and at New York’s Carnegie Hall.

In 1961, he was named host of his first network television show, which was critically acclaimed but canceled after one season. “I got an Emmy, a Peabody, and a firing notice from NBC, all in the same year,” Newhart joked.

In addition to two major sitcom successes, Mr. Newhart made occasional film appearances as a character actor, including in the 1962 Steve McQueen war film “Hell Is for Heroes.” He played the eccentric Major Major in the 1970 film “Catch-22,” based on Joseph Heller’s classic anti-war novel.

He starred in two short-lived TV sitcoms in the 1990s, “Bob” and “George & Leo,” and played Papa Elf opposite Will Ferrell in the 2003 holiday hit “Elf.” He had regular appearances on the TV shows “Desperate Housewives” and “ER,” and in 2013 he won an Emmy for his guest role as geriatric science host Professor Proton on the CBS hit sitcom “The Big Bang Theory.”

Newhart’s death at his Los Angeles home was confirmed by his publicist, Jerry Digney, but did not give a cause of death. His wife, the maiden name Virginia Quinn, died in 2023 after 60 years of marriage. He is survived by his four children, Robert, Timothy, Jennifer Bongiovi and Courtney Albertini.

Mr. Newhart continued performing as a stand-up comedian well into his 80s and made dozens of appearances on “The Tonight Show,” including frequent guest appearances with Johnny Carson. In 1992, Mr. Newhart was inducted into the Television Academy of Arts and Sciences Hall of Fame. “The Button-Down Mind of Bob Newhart” was named to the Library of Congress’ National Recording Registry as a historically significant recording in 2006.

Among his many honors, Newhart said he was especially proud to receive the Mark Twain Prize for Humor, because the first recipient was Illinoisan Richard Pryor, who several years ago, while ailing, told Newhart he’d stolen “Bob Newhart’s Button-Down Mind.”

Newhart thought Pryor was saying he’d stolen parts of the routine, but Pryor responded, “I stole your records. From a record store in Peoria, Illinois.”

“Richard, I used to get 25 cents a record,” Mr. Newhart told him. “He turned around and said, ‘Somebody give me 25 cents!'”

Pryor handed Newhart a quarter, as if to repay a debt.