A new study has found that the genetic code of a single-celled amoeba contains remnants of an ancient giant virus, providing insight into the genetic evolution of complex life. The discovery reveals that despite being potentially harmful, these viral genes are kept inactive by chemical reactions within the amoeba’s DNA. This suggests a more complex relationship between viruses and hosts, which could have implications for our understanding of the genetic evolution of other organisms, including humans.

Microbes reveal how our single-celled ancestors integrated viral DNA into their own genomes.

Researchers have found remnants of an ancient giant virus in the genome of a single-celled organism, an amoeba, suggesting that such viral sequences may have played a role in the evolution of complex life forms. The study highlights the dynamic relationship between viruses and their hosts and also has implications for human genetics.

A surprising turn of events in the evolution of complex life. Scientific advancesResearchers at Queen Mary, University of London have found that single-celled organisms closely related to animals contain remnants of ancient giant viruses within their genetic code, a discovery that provides insight into how complex organisms acquire parts of their genes and highlights the dynamic interplay between viruses and their hosts.

The study focused on a microbe called Amoebidium, a single-celled parasite that lives in freshwater environments. By analysing Amoebidium’s genome, the researchers, led by Dr. Alex de Mendoza Soler, Senior Lecturer in Queen Mary’s School of Biological and Behavioural Sciences, found a surprising abundance of genetic material from some of the largest viruses known to science. These viral sequences are highly methylated, a chemical tag that often silences genes.

“It’s like finding a Trojan horse hiding inside the shell of an amoeba.” DNA“These viral insertions are potentially harmful, but Amoeba appears to be able to suppress them by chemically inhibiting them,” explains Dr Mendoza Soler.

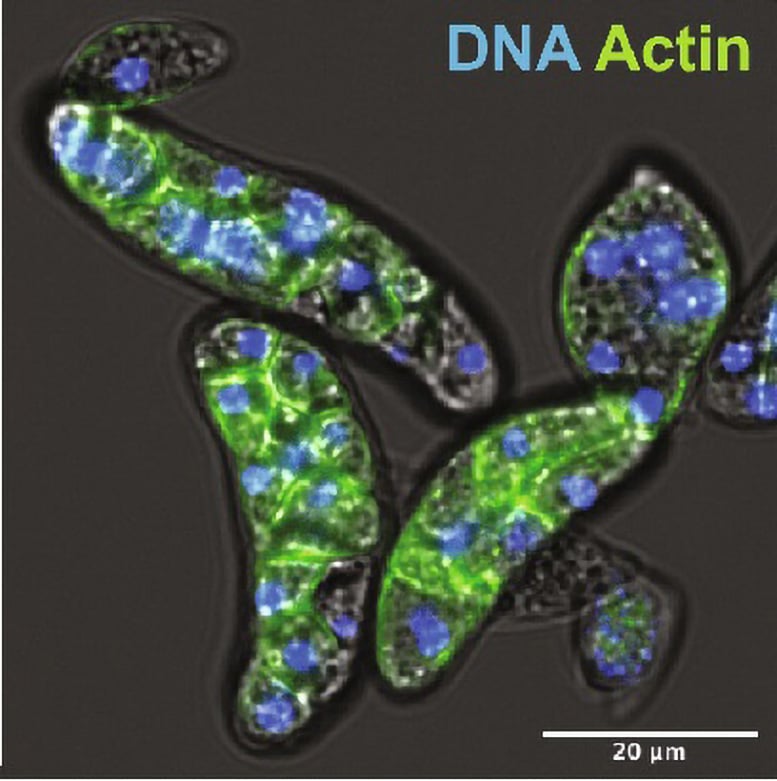

The microorganism Amoebidium appalachense undergoes its growth life cycle in the laboratory. Nuclei divide within the cells until they reach maturity (approximately 40 hours in the video), when each nucleus becomes a single cell and the colony collapses to produce offspring. Credit: Alex de Mendoza

Ongoing research and its impact

The researchers then investigated how widespread this phenomenon could be: they compared the genomes of several amoeba isolates and found a large variation in viral content, suggesting that the process of viral integration and silencing is ongoing and dynamic.

“These findings call into question our understanding of the relationship between viruses and their hosts,” says Dr. de Mendoza Soler. “Traditionally, viruses are seen as invaders, but this study suggests a more complex story: viral insertions could have played a role in the evolution of complex organisms by contributing new genes, and this is possible by chemically controlling the invader’s DNA.”

Amoebidium appalachense cells stained for DNA (blue, indicating nuclei) and actin (green) to highlight the cell membrane during the cellularization stage of the colony. Courtesy of Alex de Mendoza.

Additionally, the Amoebidium discovery shows intriguing parallels to how our own genomes interact with viruses. Like Amoebidium, humans and other mammals have remnants of ancient viruses called endogenous retroviruses embedded in their DNA. These remnants were previously thought to be inactive “junk DNA,” but some may now be beneficial. However, unlike the giant viruses found in Amoebidium, endogenous retroviruses are much smaller and human genomes are much larger. Future studies can explore these similarities and differences to understand the intricate interactions between viruses and complex life forms.

Reference: “DNA methylation drives recurrent internalization of giant viruses in their animal relatives” by Luke A. Saleh, Iana V. Kim, Vladimir Ovchinnikov, Marin Olivetta, Hiroshi Suga, Omaya Dudin, Arnau Seve Pedros, and Alex de Mendoza, July 12, 2024 Scientific advances.

DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.ado6406