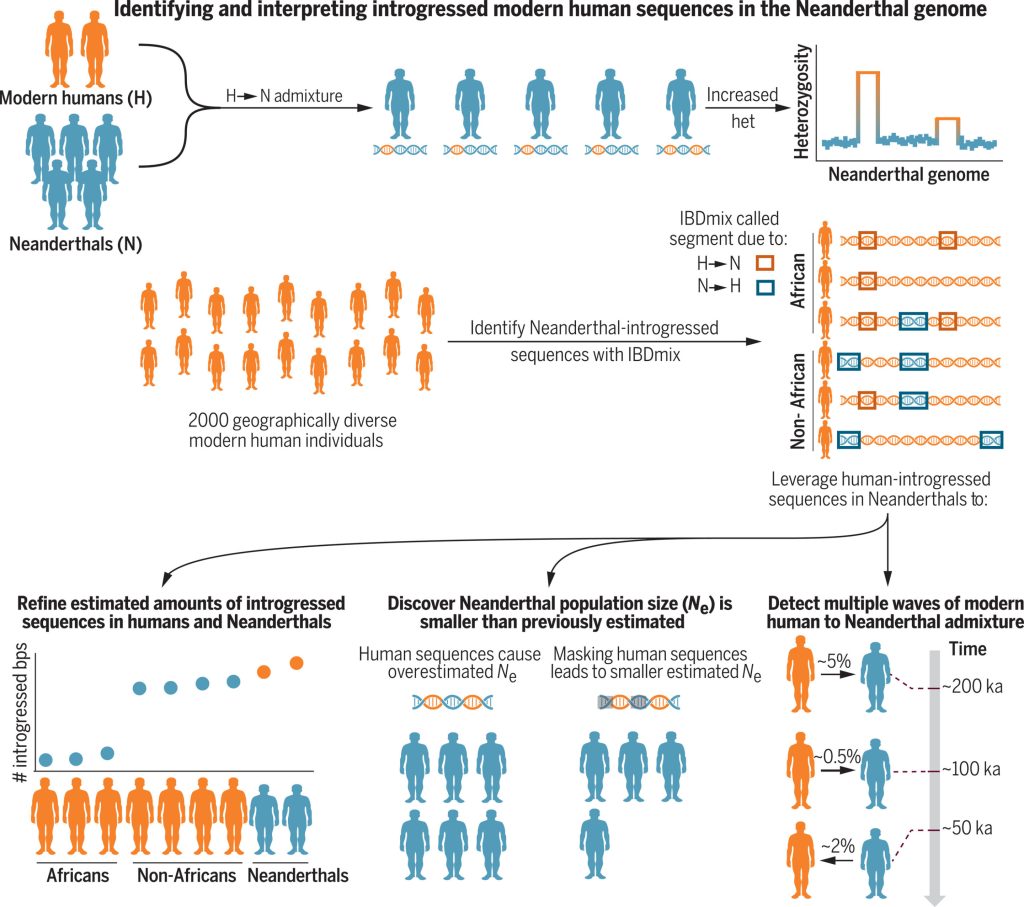

Detection of modern human to Neanderthal gene flow (H→N) and its consequences. Modern human–Neanderthal admixture caused a local increase in heterozygosity in the Neanderthal genome, a feature that enabled methods to quantify and detect introgressed sequences. Using modern human introgression sequences in the Neanderthal genome, we refined estimates of Neanderthal ancestry in modern humans by decomposing segments detected by IBDmix into those attributable to human-to-Neanderthal gene flow (H→N) and Neanderthal-to-human gene flow (N→H) in 2000 modern individuals. We also used modern human introgression sequences to estimate the effective population size of Neanderthals (Ne) than previously estimated, suggesting that a second wave of gene flow from modern humans to Neanderthals occurred about 100,000 to 120,000 years ago (ka). bps, base pairs. Credit: Science (2024). DOI: 10.1126/science.adi1768

Ever since the first Neanderthal bones were discovered in 1856, people have wondered about this ancient human race: How were they different from us? How similar were they to us? Did our ancestors live in harmony with them? Did they fight with them? Did they love them? The recent discovery of a Neanderthal-like group called the Denisovans, who lived in Asia and South Asia, raises new questions.

Now, an international team of geneticists and AI experts has added an entirely new chapter to our shared human history: Under the guidance of Professor Joshua Akey of Princeton University’s Lewis Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics, the researchers have discovered a history of genetic intermingling and exchange that suggests there were much closer connections between these early human populations than previously thought.

“This is the first time that geneticists have identified multiple waves of interbreeding between modern people and Neanderthals,” said Li-ming Li, a professor in the Department of Medical Genetics and Developmental Biology at Southeast University in Nanjing, China, who conducted the study as an associate investigator in Akey’s lab.

“We know that for most of human history, we have had a history of contact. Modern people “And Neanderthals,” Akey says. Our most direct ancestors, hominins, split off from the Neanderthal family tree about 600,000 years ago and then evolved our modern physical characteristics about 250,000 years ago.

“Modern humans continued to interact with the Neanderthals for about 200,000 years until their extinction,” he said.

of result Their research appears in the latest issue of the journal Science.

Once thought to be slow and stupid, Neanderthals are now thought to have been skilled hunters and tool makers who had sophisticated techniques for treating one another’s wounds and who thrived in Europe’s cold climate.

All of these hominin groups are human, but to avoid using the terms “Neanderthals,” “Denisovans,” and “ancient versions of our kind,” most archaeologists and anthropologists use the shorthand terms Neanderthals, Denisovans, and modern humans.

Akey and his team used the genomes of 2,000 modern humans, three Neanderthals and one Denisovan to map gene flow between human groups over the past 250,000 years.

The researchers Genetic Tools A few years ago, they designed a system called IBDmix that uses machine learning techniques to sequence genomes. Previously, researchers had relied on comparing the human genome to a “reference genome.” populationModern humans are thought to have little or no Neanderthal or Denisovan DNA.

Akey’s team found that even the populations mentioned, living thousands of miles south of the Neanderthal caves, carry traces of Neanderthal DNA that was probably carried south by voyagers (or their descendants).

Using IBDmix, Akey’s team identified a first wave of contact about 200,000 to 250,000 years ago, another wave of contact 100,000 to 120,000 years ago, and the largest wave of contact about 50,000 to 60,000 years ago.

This is the previous Genetic Data“So far, most of the genetic data suggests that modern humans evolved in Africa 250,000 years ago, stayed there for another 200,000 years, and then 50,000 years ago decided to disperse from Africa and live as humans in other parts of the world,” Akey said.

“Our model shows that, rather than a long period of stagnation, modern humans emerged and then migrated out of Africa and back again shortly after,” he said. “To me, the story is one of diffusion, and modern humans moved around a lot more than we’ve realized, encountering Neanderthals and Denisovans.”

This vision of migrating humans is consistent with archaeological and paleoanthropological studies that suggest exchanges of culture and tools between human groups.

Lee and Akey’s key insight was not to look for modern human DNA in the Neanderthal genome, but the other way around. “Much of the genetic research in the last decade has focused on how interbreeding with Neanderthals influenced modern human phenotype and evolutionary history, but these questions are also relevant and intriguing in the opposite direction,” Akey said.

They realized that the descendants of the first wave of interbreeding between Neanderthals and modern humans must have been with Neanderthals and therefore had no record in modern humans. Genetics Research“We’re now able to observe this early dispersal in a way that we haven’t been able to observe before,” Akey said.

The final piece of the puzzle was the discovery that the Neanderthal population was even smaller than previously thought.

Genetic modelling has traditionally used variation, or diversity, as a proxy for population size: the more genetic diversity, the larger the population. But using IBDmix, Akey’s team showed that a significant portion of that apparent diversity came from DNA sequences taken from modern humans, who have much larger populations.

As a result, the effective Neanderthal population dropped from about 3,400 breeding individuals to about 2,400.

Taken together, the new findings paint a picture of how Neanderthals disappeared from the record about 30,000 years ago.

“I don’t like to use the word ‘extinction’ because I think the Neanderthals were largely absorbed,” Akey said, suggesting that Neanderthal populations gradually declined and the last survivors were absorbed into modern human communities.

This “assimilation model” was first proposed by Illinois State University anthropology professor Fred Smith in 1989. “Our results provide strong genetic data that is consistent with Fred’s hypothesis, which I think is very exciting,” Akey said.

“Neanderthals have probably been on the brink of extinction for a very long time,” he said. “If their numbers have declined by 10 to 20 percent, as we estimate, that would be a major setback for an already-threatened population.”

“Modern humans were essentially waves crashing on the shore, slowly but surely eroding the coast. Eventually, we demographically overwhelmed the Neanderthals and incorporated them into the modern human population.”

For more information:

Liming Li et al., Recurrent gene flow between Neanderthals and modern humans over the past 200,000 years, Science (2024). DOI: 10.1126/science.adi1768

Provided by

Princeton University

Quote“History of Contact”: Geneticists are rewriting the story of Neanderthals and other ancient humans (July 11, 2024) Retrieved July 11, 2024 from https://phys.org/news/2024-07-history-contact-geneticists-rewriting-narrative.html

This document is subject to copyright. It may not be reproduced without written permission, except for fair dealing for the purposes of personal study or research. The content is provided for informational purposes only.