WASHINGTON — A new blood test could help doctors make diagnoses Alzheimer’s disease Researchers reported Sunday that they can detect the disease more quickly and accurately, with some methods appearing to be much more effective than others.

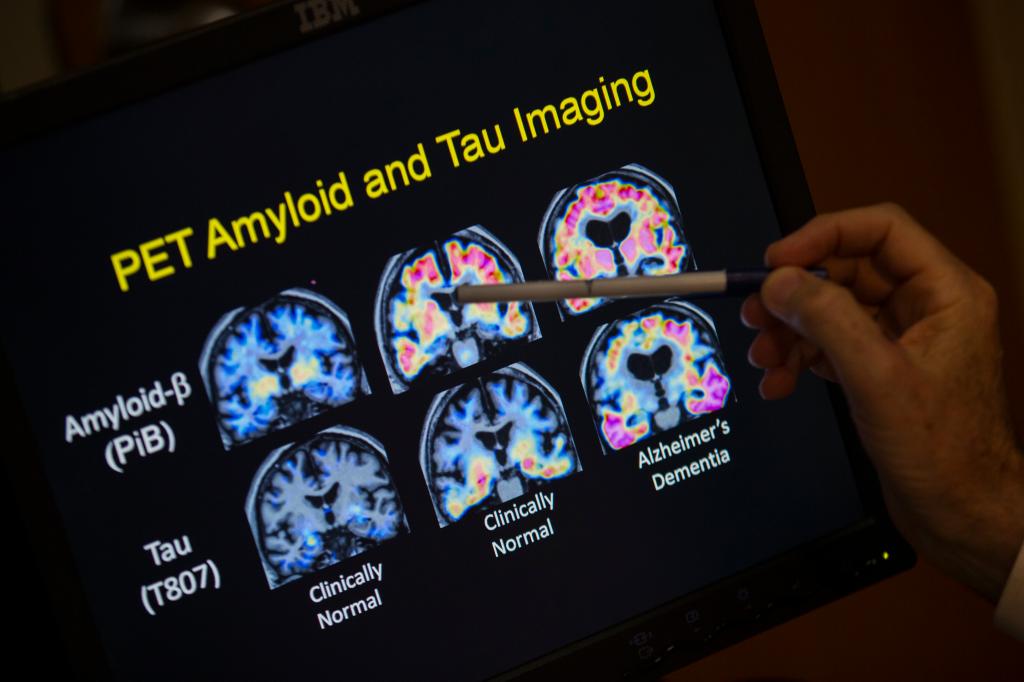

Determining whether memory loss is due to Alzheimer’s disease can be difficult. Characteristic signs of the disease Dementia, caused by the buildup of a sticky protein called beta-amyloid, is often diagnosed with difficult brain scans or uncomfortable spinal taps. Many patients are instead diagnosed based on symptoms and cognitive tests.

Laboratories are beginning to offer a range of tests that can detect certain signs of Alzheimer’s in the blood. Scientists are excited about their potential, but the tests aren’t yet widely available because there’s little data to tell doctors which types to order and when. The Food and Drug Administration has not formally approved any of the tests, and few are covered by insurance.

“What tests can you trust?” asks Dr. Suzanne Schindler, a neurologist at Washington University in St. Louis who is involved in a research project looking into this. Some tests are highly accurate, but “others are no more accurate than flipping a coin.”

There is growing demand for early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease

More than six million people in the United States and millions worldwide suffer from Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of dementia. Its defining “biomarkers” are abnormal tau proteins that cause brain-clogging amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles that kill neurons.

New drugs, Rekuenbi Treatments such as Xanla can slow the progression of symptoms somewhat by clearing the filthy amyloid from the brain. But these treatments only work in the early stages of Alzheimer’s, and it’s hard to certify patients as eligible in time. Measuring amyloid in spinal fluid is invasive. Specialized PET scans to find plaques are expensive and can take months to schedule.

Even experts sometimes have trouble determining whether a patient’s symptoms are due to Alzheimer’s disease or something else.

“We often have patients who we’re sure have Alzheimer’s disease, and they test negative,” Schindler said.

New research suggests blood test for Alzheimer’s could become easier and faster

Until now, blood tests have been used mainly in tightly controlled research settings, but a new study of about 1,200 patients in Sweden shows that the blood test can work in the hustle and bustle of a real doctor’s office — particularly for family doctors, who see many more memory-prone patients than specialists but have fewer tools at their disposal to evaluate them.

In the study, patients who visited their GP or specialist with complaints of memory problems received an initial diagnosis through conventional testing, had their blood drawn for tests, and underwent a confirmatory spinal tap or brain scan.

The blood test was far more accurate, researchers from Lund University reported Sunday at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference in Philadelphia. While initial diagnoses by primary care physicians were 61 percent accurate and diagnoses by specialists were 73 percent accurate, the blood test was 91 percent accurate, according to the study, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

What is the most effective blood test for Alzheimer’s?

Dr. John Xiao of the National Institute on Aging said the variety of tests on offer is “almost lawless,” as they measure different biomarkers in different ways.

Maria Carillo, chief science officer at the Alzheimer’s Association, said doctors and researchers should only use blood tests that have been proven to be at least 90% accurate.

Carillo and Shao agreed that the test today most likely to meet this criterion measures something called p-tau 217. Schindler, who led an unusual head-to-head comparison of several blood tests funded by the National Institutes of Health Foundation, reached the same conclusion.

Schindler explained that this type of test measures a form of tau that correlates with the amount of plaque buildup: high levels indicate a higher likelihood of Alzheimer’s disease, while low levels suggest it may not be the cause of memory loss.

Several companies are developing p-tau217 tests, including ALZpath Inc., Roche, Eli Lilly and C2N Diagnostics, which supplied the version used in the Swedish study.

Who should use the Alzheimer’s blood test?

Only doctors can order prescriptions from the lab. The Alzheimer’s Association is working on guidelines, and several companies plan to seek FDA approval to clarify appropriate use.

For now, doctors should only administer blood tests to patients with memory problems, Carrillo said, after verifying the accuracy of the type of test they order.

“For family doctors in particular, this study could be very useful in deciding who to send reassuring messages to and who to refer to a memory specialist,” said Dr Sebastian Palmqvist of Lund University, who led the Swedish study with Dr Oscar Hansson, also from Lund University.

Schindler stressed that the test is not yet available to people who have no symptoms but are worried that they may have Alzheimer’s in their family, unless it is part of their participation in a research study.

One reason is that amyloid buildup can begin as much as 20 years before the first signs of memory loss appear, and so far there are no preventative measures beyond basic advice: eat a healthy diet, exercise, and get enough sleep.But studies are underway to test possible treatments for people at high risk of Alzheimer’s, some of which involve blood tests.