SALT LAKE CITY — In a galaxy that spans light years and is more than 13 billion years old, it’s not surprising that major astronomical discoveries are few and far between. And that’s an understatement.

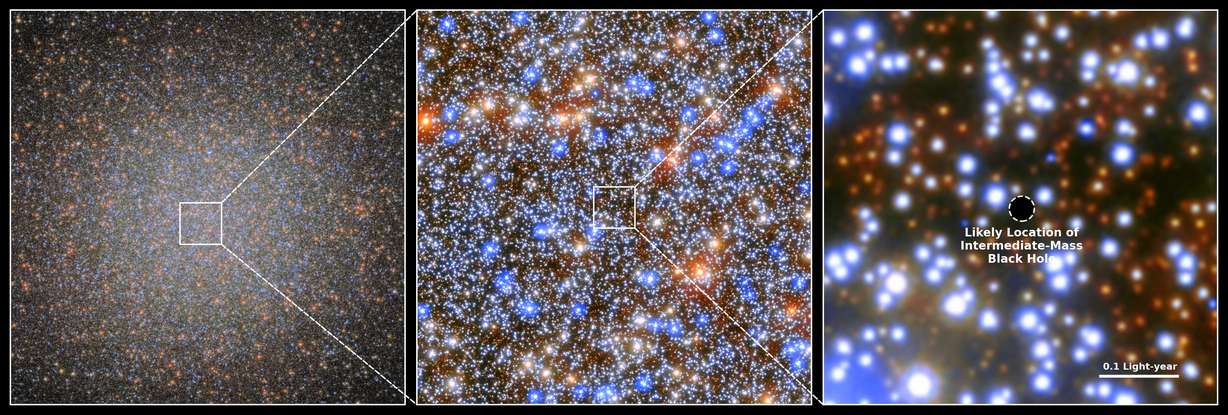

Within the Milky Way galaxy, there is a global cluster of millions of stars called Omega Centauri, which is so dense towards the center that it is impossible to distinguish individual stars, and from southern latitudes it appears as just a tiny dot in the night sky.

But within that cluster of galaxies is one that astronomers have been searching for and debating for nearly a decade, and a new study led by researchers at the University of Utah and the Mack Planck Institute for Astronomy reveals: Omega Centauri has a black hole at its center.

“This is a once-in-a-lifetime discovery. It’s been an exciting nine months. It keeps me up at night every time I think about it,” said Anil Seth, an associate professor of astronomy at the university and co-lead author of the study.

“Bigfoot level”

of studyA paper published Wednesday in the journal Nature explains that black holes come in a range of masses.

Typical black holes include stellar black holes, which have masses between one and a few tens of times that of the Sun, and supermassive black holes, which have masses several billion times that of the Sun.

Intermediate-mass black holes, like the one the team discovered, have never been clearly detected and are notoriously elusive.

“These intermediate-mass black holes are at the level of Bigfoot, so finding one would be like finding the first evidence of Bigfoot, and people would panic,” said Matthew Whittaker, an undergraduate student at the university and co-author of the study.

“Needle in a haystack”

“Omega Centauri appears to be the core of a small, independent galaxy whose evolution was interrupted when it was swallowed up by the Milky Way,” the paper says. The current state of galactic evolution suggests that these earliest galaxies should have had medium-sized central black holes that grew over time.

But how do you find them?

Seth and Nadine Neumeyer, group leaders at the Max Planck Institute and principal investigators on the study, first began working to better understand Omega Centauri’s formation history in 2019.

They realized that if they could find stars moving rapidly around the center, they could measure the black hole’s mass and finally answer questions about the black hole at the center of the galaxy cluster.

The search for this star fell to Maximilian Höberle, a doctoral student at the Max Planck Institute, who led the development of an extensive catalogue of the motions of Omega Centauri’s stars, studying more than 500 images of the cluster taken by the Hubble telescope and measuring the speeds of 1.4 million stars.

The problem with this is that most of the images Hebel had were taken to calibrate Hubble’s instruments, not to aid in groundbreaking scientific discoveries.

Still, this unintended dataset of over 500 images served a purpose.

“Finding fast-moving stars and recording their movements is like looking for a needle in a haystack,” Hebel said. In the end, Hebel not only had the most complete catalogue to date of Omega Centauri’s stellar movements, but he also found seven needles in the archival haystack — seven fast-moving stars in a small region at the center of Omega Centauri.

discovery

But the research didn’t end with the discovery of these seven stars: the researchers separated the various influences from the seven stars, each moving at a different speed and direction, and found that Omega Centauri does in fact have a central mass with a mass of at least 8,200 Suns.

Furthermore, the images show no visible object at the location of the central mass, as would be expected in the case of a black hole.

Further analysis brought even more good news for the team. As explained in the paper, one of the high-velocity stars seen in the image may not belong to Omega Centauri. It’s possible that a star outside the cluster just happened to pass just behind or in front of Omega Centauri’s center. On the other hand, the observation of seven such stars cannot be a coincidence and can only be explained by the presence of a black hole.

Checkmate.

Advance

The team plans to build on this groundbreaking discovery by further investigating the core of Omega Centauri. James Webb Space Telescope It measures the fast motion of stars approaching and receding from Earth.

As Instruments of the Future Can be deployed Pinpoint the location of the stars The goal is to determine how stars accelerate and their orbits curve with even greater precision than Hubble, but that project will be left to a future generation of researchers.

Still, the discovery lends support to the theory that Omega Centauri was the central region of a galaxy that was swallowed up by the Milky Way billions of years ago.

If you’d like to hear from the researchers in person, Seth will be presenting his team’s findings at the Clark Planetarium IMAX Theater in Salt Lake City on August 8th at 7pm. In the meantime, you can check out the full study below. online.

“I think extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, and this is really, really extraordinary evidence,” Seth said.