- Medical cannabis was legalized in 2018 after a campaign to make it available to children with severe epilepsy.

- The drug is only prescribed to a small proportion of NHS subscribers, although private clinics are seeing an increase in patient numbers.

- Activists are calling for it to be made more widely available to give patients more treatment options.

- But the government says more evidence is needed about the drug’s efficacy.

- author, Chelsea Coates

- role, BBC London

Private cannabis clinics are seeing an increase in patient numbers as more people turn to the drug to treat chronic pain and mental illnesses.

Mamedica, a medical cannabis clinic in Westminster, announced that its patient numbers had increased more than tenfold, from 250 to 2,750 in 2023.

Chief executive John Robson said this was because “we have a large number of patients who are moving to us not just from the illicit market but because they feel that the treatment the NHS can offer is not adequate for their condition”.

The majority of the clinic’s patients are taking medical marijuana to treat mental illnesses such as anxiety and depression, and 40% are taking the drug to treat chronic pain.

In a statement, the Department of Health and Social Care said: “Licensed cannabis-based medicines are routinely funded by the NHS where there is clear evidence of their quality, safety and effectiveness.”

But the report added: “The majority of products on the market are unapproved medicines and NICE clinical guidelines clearly indicate the need for further research to underpin routine prescribing and funding decisions in the NHS.”

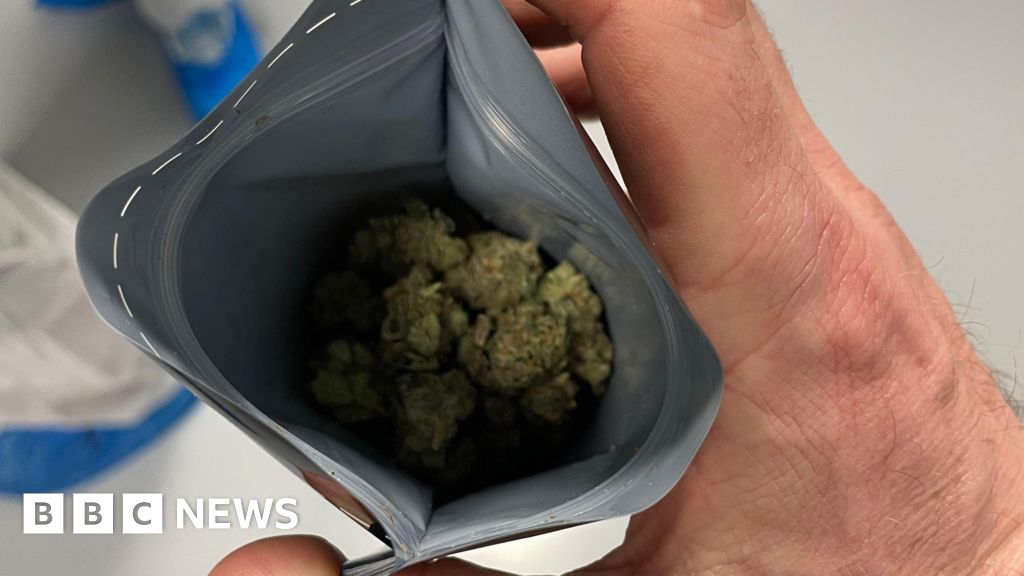

Image source, Julie Gould

One patient who takes the drug for chronic pain is Julie Gould, from Wimbledon, south London.

The 64-year-old began using medical cannabis in 2020 after being diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS) in her 30s.

“I have permanent damage. I can’t walk, it’s affected my bowels and bladder,” she said, likening one of her symptoms to “being hit in the brain with an ice pick.”

She used paracetamol and ibuprofen to dull the pain until a neurologist prescribed her the painkiller amitriptyline, which is also used as an antidepressant.

But the drug worsened the symptoms of another condition, restless legs syndrome (RLS), which causes an “unpleasant crawling or crawling sensation” in the legs.

Gould would like to see the drug “significantly subsidised”, adding that it is “too expensive for most people”, especially if it needs to be taken regularly to control symptoms.

“There should be a lot of subsidies.”

“I remember going to my GP and saying, ‘I don’t think I can get through this, I haven’t slept for two days and I really can’t cope’.

“I remember I started crying in front of her, and she looked at me and said, ‘As we get older, we all experience aches and pains.'”

Gould got a prescription from a private clinic and began taking medical cannabis oil, which he says “immediately stopped” the nerve pain.

“For me, it’s really a miracle drug,” she said, adding that it helped her get through withdrawal symptoms after being prescribed a new medication to treat her RLS.

She now only uses the medication occasionally, but worries about how she will be able to afford it if her condition worsens.

“In 2020, 100ml of the oil I was using was around £150, now the same 100ml is £350,” she says.

Image source, Getty Images

Sativex, a cannabis-based spray used to treat muscle spasms in multiple sclerosis, is licensed for prescription on the NHS but the MS Society says there is “unacceptable postcode inequity” with the drug.

NHS England already offers some cannabis-based treatments approved by the MHRA, but said “many doctors and professional bodies remain understandably concerned about the limited evidence available about the safety and effectiveness of unlicensed products”.

“Manufacturers are encouraged to take part in the UK medicines approval process, which will enable specialist doctors to use their products with the same confidence as they use any other licensed medicine recommended for use on the NHS,” the company said in a statement.

Who can take medical marijuana?

Prior to 2018, medical cannabis products could not be legally prescribed in the UK.

This is because they are classified as Schedule 1 drugs and deemed to have no therapeutic value.

This will allow NHS or private specialists to prescribe the medicine, but only if other treatments have not been effective.

Image source, Getty Images

One reason for this is that not all medical cannabis products are approved.

First, the cannabis plant contains many compounds that require it to undergo costly and complex clinical trials.

There are a few approved medical cannabis products, but they do not contain the whole plant.

Specialist NHS doctors can prescribe unlicensed products if they believe a patient would benefit, but they must apply for payment from NHS England in each individual case, which is often refused.

Private specialists can also prescribe unlicensed products, but this is often at a high cost to patients.

“There’s still a lot of prejudice.”

Image source, Drug Science

Epidemiologist Michael Linskey is leading research for Project T21, the UK’s largest not-for-profit observational study of patients taking medical cannabis.

The programme was set up by London-based charity Drug Science in 2019 and now has more than 4,600 patients taking part across the country.

This will allow patients to access medical cannabis clinics at a discounted price and will collect patient data to provide evidence on the drug’s effectiveness.

Prof Lynskey said the numbers taking part in the project had remained “relatively constant” and that there was an increase in the number of people requesting cannabis prescriptions across the UK, particularly among patients over 65.

Around a third of patients in the UK have tried the drug to treat mental illnesses such as anxiety and PTSD, but charities say this is still an “emerging area”.

The UK’s medical cannabis market is the second largest in Europe and is expected to be worth £300 million by 2025, according to market research firm Prohibition Partners.

Prof Linskey said it was “unfortunate” that some people were being “excluded” from private clinics because of the cost of cannabis, especially as many people with chronic conditions “are not working, or not working full time and are struggling financially”.

He says it may take longer for attitudes to medical cannabis to change, even if the drug becomes more available on the NHS.

“There is still a lot of stigma around sexual activity among the general public, including many doctors who don’t know it’s legal or don’t believe it should be legal,” Prof Linsky said.

“Don’t tell anyone.”

For Steven (not his real name), finding out that an employer or coworker is using medical marijuana is “one of my biggest fears.”

“I don’t tell anyone, it’s a secret,” says the 52-year-old software developer from London.

He first tried the drug in 2022 after receiving a prescription from a private clinic through the T21 project.

Like most other patients, he had to prove that he had already been prescribed at least two types of treatment which had not worked, and he now sees a private GP every three weeks to have his treatment reviewed.

Image source, Getty Images

A single session costs £60, with a further £80-180 for a supply of medical cannabis oil.

“I’m very lucky because I can afford this and I have a good job, but there are a lot of people who will really struggle to pay for this,” he told the BBC.

Stephen is one of a growing number of people turning to medical cannabis to treat their mental health.

According to the T21 Project, 42% of patients in the program are taking medication for mental health issues, making them the second largest group after chronic pain patients.

After attempting suicide in his late teens, Stephen was diagnosed with what was then called “bipolar depression” and was prescribed a series of antidepressants on and off until he was 49.

“I felt like a zombie,” he said, adding that the SSRIs he was prescribed “seemed to increase my anxiety.”

“At one point I was prescribed benzodiazepines to treat my anxiety and I became completely dependent on them. It took me about two years to try and get off the medication.”

Image source, Getty Images

After a two-year wait, he was finally diagnosed with autism, PTSD and anxiety.

He began taking medical cannabis oil soon afterwards, which he said was “transformative” and helped him cope with the “hectic environment” at work.

“It also had the odd effect of making me more empathetic towards families,” he added.

He says he understands medical marijuana doesn’t work for everyone, but he wants to ensure people with complex mental illnesses have access to a wider range of treatments.

“I wouldn’t necessarily claim that it works for everyone, because I think that’s always a dangerous claim, but I think it’s always good to have options.”

Despite this, he says the fear of being found out for using legal drugs remains “terrifying.”

“There’s a huge stigma attached to cannabis because of its recreational use status.”

Some activists also argue that this stigma is a major obstacle to making medical marijuana more accessible to those who could benefit from it, especially in minority communities.

Katrina French is the founder of UNJUST, a nonprofit organization that campaigns against discriminatory practices in police and the criminal justice system.

She said it was “fantastic” that people could access medicinal cannabis on the NHS, but argued “more needs to be done”.

“What we’re seeing is the continued criminalization of Black communities around cannabis use. It’s very hard to encourage communities to seek out cannabis for medicine when their use in other areas is criminalized, so there’s a lot of conflicting messaging.”

‘Lack of clinical evidence’

In a statement, the Department of Health and Social Care said further research into its effects was needed before making any changes to the way medical cannabis is prescribed on the NHS.

“Until the evidence base improves, prescribers will be reluctant to prescribe and the NHS will be unable to make routine funding decisions.”

“That’s why we continue to urge manufacturers of these unlicensed products to conduct their research and we are working closely with regulators, research organisations and NHS partners to carry out clinical trials to test the safety and effectiveness of these products.”

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) is responsible for deciding which medicines are available on the NHS.

The group said its clinical guidelines reflect the “overall lack of clinical and cost-effectiveness evidence” for cannabis-based medicines and encourage specialists to consider “the relative risks and benefits when choosing a treatment.”

He added that because the majority of cannabis-derived products are unlicensed, “it is important to point out that even if NICE recommends the widespread use of these products, this does not necessarily mean that they will become routinely available on the NHS”.