NASA announced Wednesday that it is canceling the VIPER (Volatile Investigation Polar Rover) project. This is the second time in less than a decade that the space agency has canceled plans for a roving spacecraft to search for water ice on the moon. The decision comes six years after the cancellation of a similar mission, Resource Prospector.

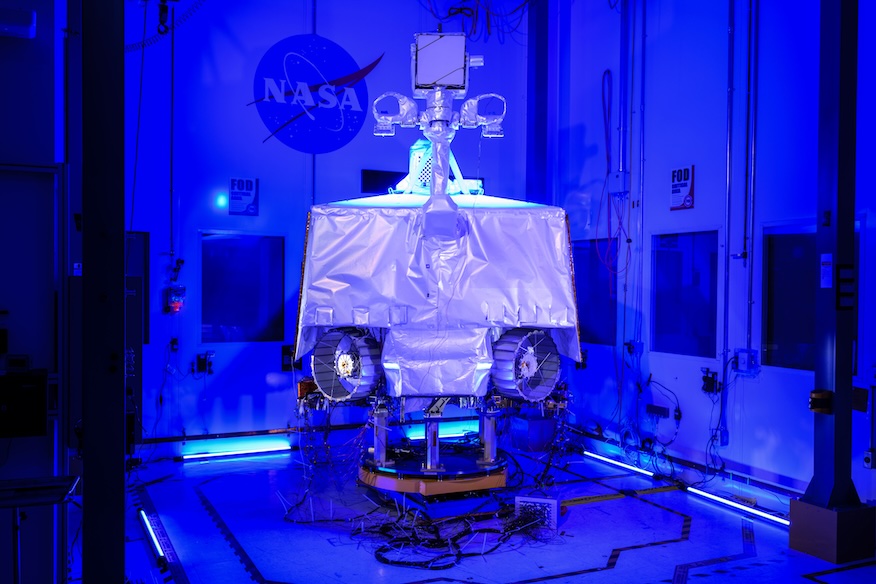

The 430-kilogram (948-pound) rover is designed to fly to the moon’s south pole aboard Pittsburgh-based Astrobotic’s Griffin lander, the company’s second planned mission to the moon. Astrobotic’s first mission, the smaller Peregrine lander, ended early in January after propulsion problems prevented it from reaching the moon.

Joel Karns, associate administrator for exploration for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, said in a conference call with reporters that rising costs were a major factor in the cancellation of the VIPER program.

“When we formalized the VIPER project, we told Congress that the project was budgeted at $433.5 million and that landing would occur at the end of 2023,” Kearns said. “We had already decided to reschedule the landing to 2024 to allow Astrobotic to perform additional propulsion testing of the lander.”

“When we made that decision, we updated the VIPER workplan and reset the budget at $505.4 million, with a planned landing at the end of 2024. However, updated estimates made earlier this year projected the VIPER project to cost $609.6 million, as the plan to land VIPER at the end of 2024 was no longer in place and the mission would instead need to land during the 2025 science window.”

Kearns said going over 30% of the original budget was an overreach and triggered what was called an automatic cancellation review, which took place in June. First PublishedNASA initially estimated the rover, about the size of a gold wagon train, would cost $250 million and be delivered to the lunar surface in 2022.

In a May 2024 blog post, VIPER project manager Dan Andrews shared that the lander passed its Systems Test Readiness Review in April, allowing VIPER to move on to stress and environmental testing.

“These environmental tests are important because they expose the rover to conditions it will encounter during launch, landing, and the thermal environment of operations at the lunar south pole,” Andrews wrote in May. “Specifically, the acoustic tests will simulate the harsh, vibration-heavy ‘rock concert’-like experience during launch, and the thermal vacuum tests will expose VIPER to the hottest and coldest temperatures it will encounter during the mission while operating in the vacuum of space. This is a tough job, but we have to see if we’re up to it.”

Kearns said in his comments Wednesday that VIPER has not yet completed systems-level environmental testing and that some of the ground systems needed to operate the rover on the lunar surface are still incomplete.

He said canceling VIPER would save NASA at least $84 million, “which is the cost of completing the roads for the flight and ground systems and then continuing to operate the mission, which now cannot be done in 2024.”

When asked why such a decision was made, given that NASA has weathered similar or greater budget increases before and has never canceled a program, Karns said that not only is the agency bound by Congressional budget constraints, but that the estimates cited may not be the end of the story.

“One of the concerns we had was the immediate cost of having to take away from other parts of NASA’s science research to prepare for the September 2025 landing, but the other concern was that if the landing doesn’t happen in September 2025, but happens later than November, it will probably be in 2026 and we would probably need the same amount of funding to continue through 2026,” Kearns said.

A notable part of the concern about the timeline stemmed from the fact that Kearns said the Griffin lander would be ready no sooner than September 2025.

“We also took into account the possibility that the launch of the Griffin lander could be delayed beyond September 2025. If the Griffin lander itself could not launch by November 2025, it would miss the VIPER science operation period, which is a 100-day mission after landing,” Kearns said. “VIPER can only make measurements when there is enough sunlight in certain conditions in Antarctica – what we call the Antarctic summer – and it also has a way to wirelessly communicate directly to Earth.”

“This is a challenge for long-term missions to Antarctica that don’t use nuclear energy for heating or power,” Kearns added. “We have to be very careful about the amount of time we spend in darkness.”

Now what happened?

NASA plans to retain its $323 million contract with Astrobotic, which will keep Griffin Mission One moving forward with a launch date in 2025. Kearns said the lander will travel to the moon carrying a mass simulator roughly the same weight as VIPER.

He added that Astrobotic could carry additional commercial payloads on the lander and, if necessary, could scale down the size of the Mass Simulator to compensate.

“Given the scope, schedule and cost of Griffin, and the fixed price we agreed to with Astrobotic for Griffin, NASA has decided not to substitute additional science instruments for Griffin because doing so could potentially result in schedule delays and increased costs to the government,” Kearns said. “So our focus right now with Griffin is getting data from a successful landing, data on how the propulsion system performs.”

Asked whether VIPER could switch to another lunar lander NASA has reserved, such as a cargo version of Blue Origin’s Blue Moon lander, Nicola Fox, associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, said doing so could negatively impact the budgets of other CLPS missions.

“This is about cost risks and threats to the rest of NASA’s programs,” Fox said.

She said NASA has informed congressional budget writers of its decision and is awaiting their response.

Astrobotic said in a post on X (formerly Twitter) that it aims to launch its Griffin lander in the third quarter of 2025. In April, the company announced it would partner with Mission Control to launch its own shoebox-sized rover, called a Cube Rover, as part of Griffin Mission One.

The lander will also carry the LandCam-X payload, commissioned by the European Space Agency and French start-up Lunar Logistics Services, which is designed to “take photographs during approach to the Moon in order to improve the accuracy and safety of future lunar landings.”

Astrobotic has not yet released a complete list of its commercial customers.