aMore than 7,500 clinicians and researchers gathered in Philadelphia Alzheimer’s Association International ConferenceEvery year, researchers come together to discuss new treatments for Alzheimer’s disease, with fierce debates over when to prescribe new drugs to treat the disease. Lekanemab (Rekenbi) was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2023, but Negative recommendation It was approved by the European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use last week. Approved by the FDA in July.

Both have significant health and economic implications that could affect the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and, depending on the neurologist’s position, the diagnosis that patients receive.

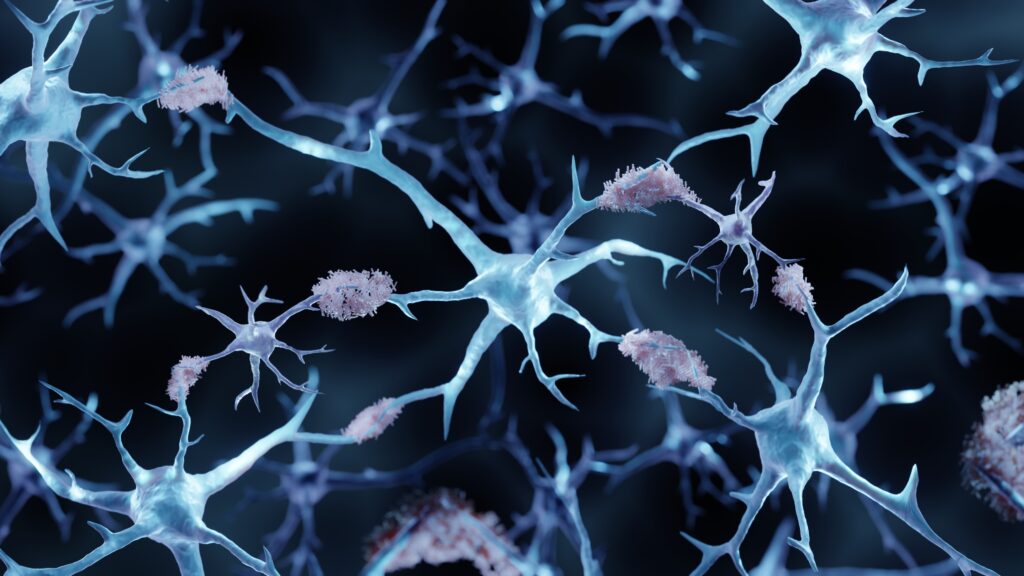

At the heart of the disruption is a harmful protein called beta-amyloid in the brain. In Alzheimer’s disease, deposits of this protein, called plaques, impede brain function, affecting memory and cognition.

We are physicians specializing in Alzheimer’s research and treatment. To better understand how our field perceives the new treatment environment that has attracted attention, progress and serious debate over the past two years, we conducted a survey of 268 neurologists in the United States and Europe on June 14, 2024 using an online platform in collaboration with Sermo, a social network for physicians.

of result Significant divides were revealed: 59% of U.S. neurologists support amyloid-targeted therapies (such as the two approved therapies), but 41% are skeptical due to past failures and side effects, and only 5% consider changes in biomarkers (such as imaging or blood tests that measure reduction in amyloid plaques) as a measure of clinical benefit.

is more than 47 million Americans This is when amyloid builds up silently and there are high levels of amyloid plaques in the brain, even though there is no memory loss or cognitive impairment. Neurologists call this preclinical Alzheimer’s disease.

With the advent of amyloid plaque-clearing monoclonal antibodies such as donanemab and lecanemab, and others in the pipeline, Alzheimer’s treatments are A $30 billion industry in the next decade It could bring about entirely new ways of thinking about and treating dementia.

But our survey of neurologists revealed deep divisions within the medical community. These rifts are influenced by geographic location, differing theories about the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease, and concerns about serious side effects, such as brain hemorrhages, associated with these new drugs.

No matter where people live, the chances of finding a neurologist willing to prescribe an amyloid-targeting treatment for preclinical Alzheimer’s are about as likely as a coin toss, which would be off-label, meaning it’s used outside of its FDA-approved uses.

Our survey found that just over half of neurologists in the US and Europe are ready to diagnose Alzheimer’s based on blood biomarkers before symptoms appear and prescribe new drugs such as Leqembi and Kisunla without needing FDA approval. The other half remain skeptical, given the failure of amyloid-targeting drugs in clinical trials and their reluctance to replace clinical assessments with biomarkers.

The Department emphasizes that there is an urgent need for robust evidence demonstrating the reliability of beta-amyloid biomarkers in the diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease.

Depending on your location, the likelihood of finding a doctor willing to prescribe anti-amyloid treatments varies: these anti-amyloid drugs are not commercially available in Europe, but 83% of European neurologists accept the newer therapies as standard of care, compared with only 59% of US neurologists, reflecting large regional differences in perception and possibly practice.

Nearly half of U.S. neurologists are skeptical in part because they would like to see more robust evidence of the drug’s effectiveness. Of note, 95% of neurologists overall do not consider biomarker changes a measure of clinical benefit, instead placing more emphasis on cognitive and functional benefits and reductions in the volume of the hippocampus (the brain’s memory center) than on plaque reduction. This skepticism is reflected in the low adoption rate of anti-amyloid therapies in the U.S. Of the millions of Americans with early-stage Alzheimer’s who could be candidates for this therapy, Estimated from the register Since it received FDA approval and Medicare coverage began in July 2023, only about 10,000 people have been prescribed Leqembi.

In our survey, 71% of neurologists are very concerned about the possibility of serious side effects such as brain swelling and microbleeds (called amyloid-related imaging abnormalities, or ARIA), which further complicates the decision to prescribe these new therapies. Notably, 8% of U.S. neurologists feel they would never use these therapies because the risks are too dangerous. An additional 28% are also seriously concerned about the greater loss of brain volume associated with amyloid-targeting antibodies.

This gap between professionals has a direct impact on patient care, and treatment choices can vary greatly depending on a physician’s position on a new treatment.

Anyone who knows the 45 million people living with Alzheimer’s worldwide would do anything to stabilize symptoms or slow the cognitive decline caused by the disease. This ongoing debate over treatment highlights the need for conclusive research to validate biomarker discoveries and a push toward harmonization of treatment approaches to ensure consistent and effective patient care.

Improving patient care and unifying the field of neurology requires informed decisions based on comprehensive data. We call on companies developing and marketing anti-amyloid therapies to fully disclose their clinical trial databases so that physicians and researchers can better understand the potential risks and benefits of these drugs.

For example, there is limited evidence that amyloid plaque reduction directly correlates with outcome. However, treatment guidelines for donanemab recommend stopping treatment once plaque levels normalize. Open access to these datasets will enable dementia experts to confirm the validity of this biomarker-based treatment endpoint.

While researchers funded by pharmaceutical companies and the National Institutes of Health may be reluctant to share data for fear of misuse, the benefits of transparency outweigh these concerns. Distrust of commercial motives, fueled by a divisive political climate, may be mitigated by greater openness. Sixty percent of Americans believe prescription drugs have improved their lives, yet 80% believe They stress that pharmaceutical companies are putting profits above patients and that transparency is needed to improve public perception.

Reducing disparities in Alzheimer’s care is crucial to avoid inconsistent treatment and care that causes many eligible individuals to lack access to potentially transformative medicines. By publishing more clinical trial data, pharmaceutical companies can restore public trust and help healthcare providers overcome knowledge gaps that lead to inconsistent treatment recommendations.

The European Medicines Agency refused to approve Lukembi, saying the small clinical benefits seen with the drug were “not sufficient to outweigh the risk” of brain swelling and bleeding severe enough to require hospitalization in some patients.

We, and many of our colleagues, will be waiting to see whether the remarkable enthusiasm of European neurologists expressed in this survey will be enough to reverse the European Medicines Agency’s stance, or whether more outcomes and safety data will be needed, as we have called for.

Murali Doraiswamy, MBBS, is Professor of Psychiatry and Geriatrics at the Duke University School of Medicine and a member of the Duke Brain Science Institute. Lon S. Schneider, MD, is Professor of Psychiatry, Neurology and Geriatrics at the University of Southern California and the Della Martin Professor of Psychiatry and Neuroscience at USC. The authors Selmo We thank the neurologists who participated in the International Survey of Neurologists for their contributions. Both authors have served as consultants for government agencies, pharmaceutical companies, and advocacy groups in this field, but this study was not funded by any company.