Prehistoric humans hunted mammoths, and a growing body of research shows that this species, along with at least 46 other species of large herbivores, were driven to extinction by humans. Credit: Sculpture by Ernest Gliese; photo by William Henry Jackson. Courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

The researchers Aarhus University They conclude that human hunting, not climate change, has been the main driver of large mammal extinctions over the past 50,000 years. The findings are based on a review of more than 300 scientific papers.

During the past 50,000 years, many large seedLarge animals weighing more than 45 kilograms, such as wolves and wild boars, became extinct. Research from Aarhus University suggests that these extinctions were primarily caused by human hunting, rather than climate change, despite the fact that there was significant climate change during this period. This conclusion is supported by a comprehensive review incorporating evidence of human hunting, archaeological data, and research from a range of scientific disciplines, demonstrating that human activity was a more decisive factor in these extinctions than earlier dramatic climate changes.

A fierce debate has raged for decades: Was it humans or climate change that caused the extinction of many species of large mammals, birds and reptiles that disappeared from the face of the Earth over the past 50,000 years?

By “large,” we mean large animals weighing at least 45 kilograms. At least 161 mammal species became extinct during this period, based on fossils discovered so far.

The hardest hit have been the megaherbivores, terrestrial herbivores weighing more than a ton. 50,000 years ago there were 57 species of megaherbivores, but today there are only 11. The remaining 11 species have also experienced dramatic declines in population, but they are not completely extinct.

A research group from the Danish National Research Foundation’s Centre for Novel Biosphere Ecological Dynamics (ECONOVO) Aarhus University It is now concluded that many of these extinct species were hunted to extinction by humans.

Jens Christian Svenning looks at the fossil skeleton of a giant ground sloth, Lestodon almatus, at the Natural History Museum in New York. Photo by Els Maggard, Aarhus University.

Various research fields

They published their conclusions in a commissioned review article published in a scientific journal. Cambridge Prism: ExtinctionA review article synthesizes and analyzes existing research in a particular field.

In this case, researchers from Aarhus University drew on several research fields directly related to megafauna extinctions, including:

- Timing of species extinction

- Animal food preferences

- Climate and habitat requirements

- Genetic estimates of past population sizes

- Evidence of human hunting

Additionally, we have incorporated a wide range of research from other disciplines that are necessary to understand the phenomenon.

- Climate history over the past 1 to 3 million years

- Vegetation history over the past 1 to 3 million years

- Evolution and dynamics of faunas over the past 66 million years

- Archaeological data on human expansion and lifestyle, including dietary preferences

Climate change didn’t play a big role

The dramatic climate changes during the last interglacial and glacial periods (known as the Late Pleistocene, between 130,000 and 11,000 years ago) certainly affected the abundance and distribution of large and small animals and plants around the world, but only large animals, and especially the largest, experienced significant extinctions.

A key observation is that similarly dramatic glacial and interglacial periods over the past few million years have not caused selective extinctions of large animals. At the beginning of each glacial period, in particular, the new colder, drier conditions caused large-scale extinctions in some areas, such as of trees in Europe, but there was no selective extinction of large animals.

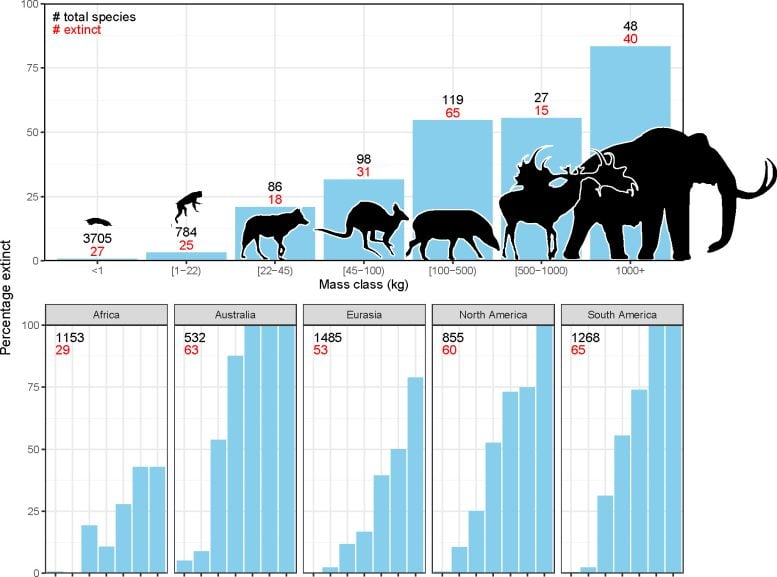

This diagram shows how the extinction of large mammals during the Late Quaternary relates to body size. At the top, you see the global percentage of species that went extinct based on body size. At the bottom, it’s broken down by continent. The black numbers represent the total number of species alive during this period, including species still living today and those that have gone extinct. The red numbers show species that have gone extinct. Credit: Aarhus University ECONOVO / Cambridge PRISM: Extinction

“The massive and selective extinction of megafauna over the last 50,000 years is unique in the last 66 million years. Previous climate changes have not led to such mass and selective extinctions. This supports the argument that climate played a major role in megafauna extinctions,” says Professor Jens-Christian Svenning, head of ECONOVO and lead author of the paper. He adds: “Another important pattern supporting the argument that climate played a role is that recent megafauna extinctions have hit climatically stable and unstable regions equally hard.”

A skilled hunter and a fragile giant

Archaeologists have found traps designed to hunt very large animals, and isotope analysis of protein residues on ancient human bones and spear points reveals that they hunted and ate the largest mammals.

Jens Christian Svenning adds: “Early modern humans were able to effectively hunt even the largest animal species and clearly had the ability to reduce large animal populations. These large animals were, and remain, particularly vulnerable to overexploitation because they have long gestation periods, give birth to very small numbers of offspring and take many years to reach sexual maturity.”

The analysis found that human hunting of large animals, such as mammoths, mastodons and giant sloths, was widespread and consistent around the world.

It has also been shown that the species became extinct at very different times and at different rates around the world – in some areas it went extinct very quickly, whereas in others it took more than 10,000 years – but everywhere the extinction occurred after the arrival of modern humans or, in the case of Africa, after cultural advances had taken place among humans.

…in any environment

Species became extinct on every continent except Antarctica, and in every type of ecosystem, from tropical forests and savannas to Mediterranean and temperate forests and steppes, to Arctic ecosystems.

“Many of the extinct species were able to thrive in a variety of environments, so their extinction cannot be explained by climate change causing the disappearance of a specific ecosystem such as the Mammoth Steppe, which also hosted only a few large animal species,” explains Jens Christian Svenning. “Most species lived in temperate to tropical conditions and would in fact have benefited from the warming at the end of the last ice age.”

Results and Recommendations

The researchers point out that the decline of large animals has had significant effects on ecosystems. Large animals play a central role in ecosystems by influencing vegetation structure (e.g. the balance between dense forests and open spaces), seed dispersal and nutrient cycling. The loss of large animals has led to major changes in ecosystem structure and function.

“Our results highlight the need for active conservation and restoration efforts. Reintroducing large mammals can help restore ecological balance and support the biodiversity that evolved in megafauna-rich ecosystems,” says Jens-Christian Svenning.

Reference: “Late Quaternary megafauna extinctions: patterns, causes, ecological impacts and implications for ecosystem management in the Anthropocene” by Jens-Christian Svenning, Rhys T. Lemoine, Juraj Bergman, Robert Buitenwerf, Elizabeth Le Roux, Erick Lundgren, Ninad Mungi and Rasmus Ø. Pedersen, 22 March 2024, Cambridge Prism: Extinction.

DOI: 10.1017/ext.2024.4

The research was funded by Villum Fonden, the Danish National Research Foundation and the Danish Fund for Independent Research.