One of the scariest things about a diagnosis is Alzheimer’s disease The disease means both patients and caregivers never know what will happen next, but new research offers hope of shedding light on prognosis.

A team of experts has developed a tool that can predict the cognitive decline over the next five years in patients showing early symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease.

The progression of dementia VariesBut by carefully studying real patients, researchers were able to outline a predictive model.

“People are so interested in what will happen to them and their loved ones with the disease that they are facing, that better predictive models are urgently needed.” Physician and researcher Peter van der Veele explains: of the University of Amsterdam in the Netherlands.

Van der Veer and his colleagues studied 961 patients with an average age of 65 years. Of those, 651 had mild dementia and 310 had mild cognitive impairment. Each patient also had: Amyloid beta plaqueProtein deposits in the brain Characteristics of Alzheimer’s Disease disease, The most common dementia.

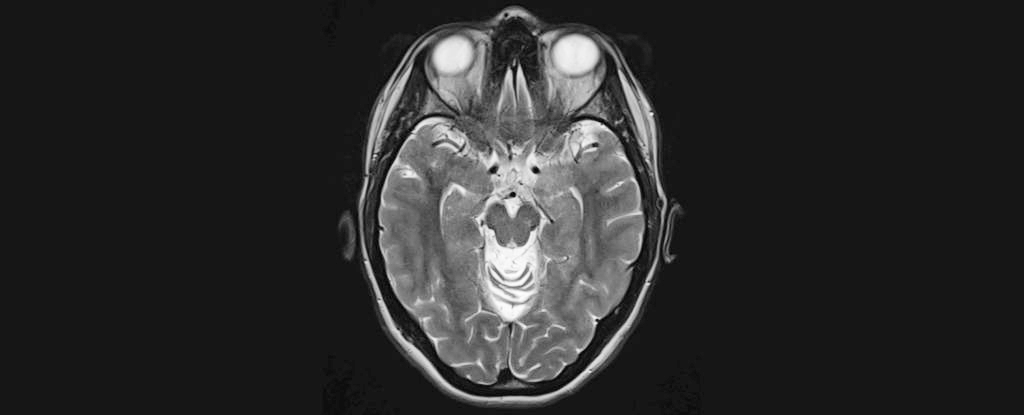

They carefully analyzed MRI The team relied on scans and biomarkers taken from cerebrospinal fluid, taking into account the patient’s age, sex, medical history, and scores over time on cognitive tests rated on a 30-point scale.

A test score above 25 indicates no dementia, 21-24 is considered mild dementia, 10-20 moderate dementia, and below 10 severe dementia.

The results showed that people with mild cognitive impairment started out with an average score of 26.4 and after five years their score had dropped to 21. But people with mild dementia progressed much faster, dropping from 22.4 to 7.8 over the five-year period.

The researchers also medicine.

“This will be even more important in the future if we can treat Alzheimer’s disease.” “We have a lot of potential for improvement,” says neuroscientist Wiesje van der Vliet. of the University of Amsterdam.

“This can be a starting point for a discussion between doctor, patient and family about the pros and cons of treatment so that appropriate decisions can be made together.”

According to the model, a patient with mild cognitive impairment and a baseline cognitive test score of 28 could reach moderate disability after six years. If they were given a drug that reduced the rate of decline by 30 percent, it would take them 8.6 years to reach moderate disability.

For someone with mild dementia and a starting score of 21, it would take 2.3 years to reach moderate disability, or 3.3 years if progression was slowed with drug therapy.

The actual scores varied considerably, with only half of the cognitively impaired patients scoring within two points of the predicted value, and half of the dementia patients scoring within three points. This suggests that although the model is useful in informing patients about cognitive decline, obtaining a definitive prognosis can be difficult.

But the findings are promising: By including as many parameters as possible, and as long as healthcare professionals are clear about the uncertainties, the model can produce customized outcomes and provide patients and their families with more information about what will happen as the disease progresses.

Meanwhile, scientists hope that they can further refine their research in the future to produce better predictive models.

“We know that people with cognitive impairments and their caregivers are most interested in answers to questions like, ‘How long can I drive a car?’ or ‘How long can I pursue my hobbies?'” van der Veere says.

“We hope that in the future, our models will help predict these questions about quality of life and functioning in everyday life. But until then, we hope that these models will help doctors translate the predictive scores into answers to people’s questions.”

This study Neurology.