Researchers have discovered that a currently endangered flightless bird in New Zealand is taking refuge in an area once home to six moa species before they went extinct — a finding that could have major benefits for conservation efforts.

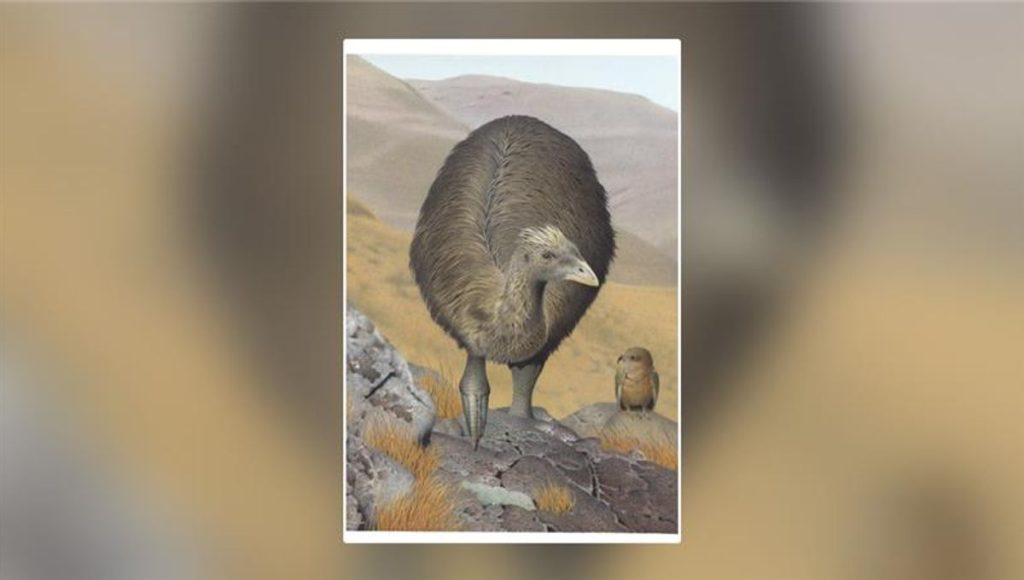

Moas (Dinornithiformes) are a group of large flightless birds that once lived in New Zealand, but current fossil evidence suggests that this unusual, large bird of prey became extinct within the second century AD. The Coming of Man In their environment about 800 years ago.

Before they went extinct, moas retreated to the same cold, isolated mountainous regions where today’s critically endangered flightless birds are found, such as Mount Aspiring in the South Island and the Ruahine Ranges in the North Island, according to a new analysis.

“Moa populations were likely first to disappear from the highest quality lowland habitats favoured by Polynesian settlers, and the rate of population decline decreased with elevation and distance moved inland,” lead author Dr Sean Tomlinson said in the paper. statement.

“By identifying the last remaining populations of moa and comparing them with the distribution of flightless birds in New Zealand, we found that these last refuges also protect many of the populations of takahe, weka and great spotted kiwi that survive today.”

Tomlinson and his colleagues achieved this by combining evidence from the fossil record and paleoclimatic information with sophisticated computational models. They also analysed and reconstructed human migrations as they arrived in New Zealand and expanded outwards.

“Our study overcame previous logistical challenges, allowing us to track the population dynamics of six moa species at a resolution previously thought impossible,” added lead author Dr Damian Fordham.

“Our study shows that despite significant differences in the ecology, demographics and timing of extinction of moa species, their distributions collapsed and converged to the same regions in the North and South Islands of New Zealand.”

Factors causing the decline of existing native flightless birds in New Zealand include: moreThis study shows that their spatial dynamics are very similar.

“The main commonality between past and present refuges is not that they are the best habitats for flightless birds, but that they remain the last remaining refuges, having been the least affected by humans,” explained co-author Dr Jamie Wood.

“As with previous waves of Polynesian expansion, European habitat conversion across New Zealand, and the spread of the animals they introduced, was directional, moving from the lowlands into the less hospitable cold mountain areas.”

“This study not only provides a valuable new tool for understanding past extinctions on these islands, where fossil and archaeological data are limited, but also shows that even species that went extinct long ago can provide insights for conservation efforts today. Now, more than ever, it is important that people in New Zealand and beyond protect the remote wilderness areas where endangered animals find refuge.”

This study Natural Ecology and Evolution.