Lupus is, in superhero terms, a tale of disaster: A loyal hero turns bad and tries to destroy his allies. But new research begs the question: what if immune cells could revert to being good and actually help save tissues damaged by autoimmune disease?

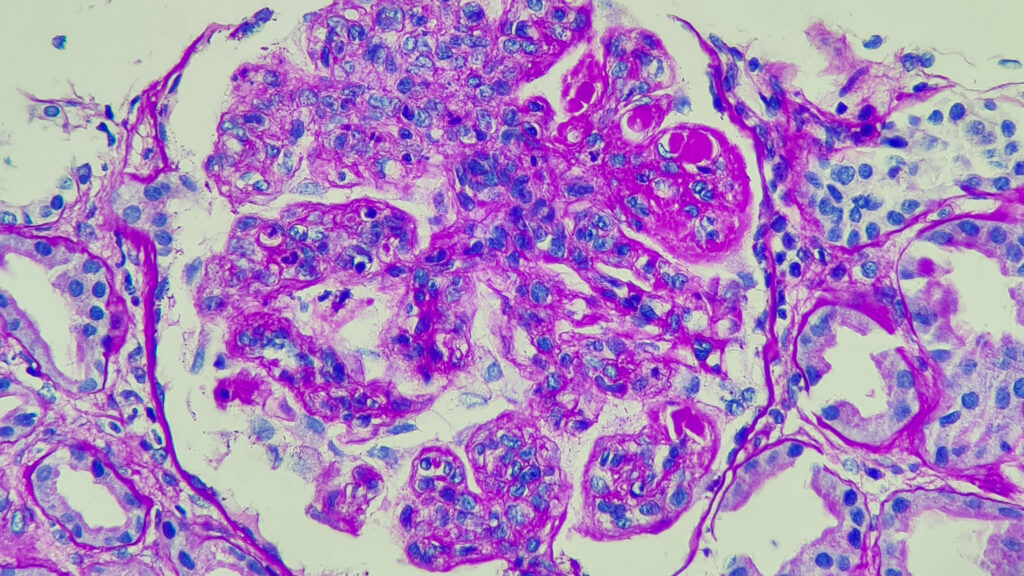

Lupus is complicated because it turns the body’s own defenses against itself, causing a continual immune misfire. B cells and T cells are white blood cells that identify and destroy pathogens in the body. They work together. T cells make a protein called CXCL13, which calls B cells to sites of inflammation. In diseases like cancer, more CXCL is a good thing because it attracts B cells to the site of malignancy, amplifying the immune system’s response. With lupus, B cells are recruited to places they shouldn’t be, like the skin, lungs, and kidneys.

More than 200,000 adults in the United States are thought to have systemic lupus erythematosus, the most common type of lupus. As the immune system attacks healthy tissue, lupus can cause organ damage and symptoms such as joint pain, fatigue and facial rash. For decades, scientists have tried to understand what causes the disease, which most often affects women and girls.

The data shows that many lupus patients also have another imbalance: Compared with non-autoimmune patients, lupus patients have fewer T cells that make a protein called interleukin-22, which helps with inflammation and wound healing. This creates a double disadvantage: fewer helpful cells and more cells that promote damage, said Jae-hyuk Choi, an associate professor of dermatology, biochemistry and molecular genetics at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

“We wondered if there was a molecular switch that controlled how cells switched between these two,” said Choi, the study’s senior author. Published in Wednesday’s issue of Nature magazineChoi, along with a team of researchers and co-author Deepak Rao, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, discovered the switch.

The cells can “naturally see-saw” between two phenotypes — beneficial IL-22-producing cells and harmful B-cell support cells — and scientists may be able to tip the scales in favor of beneficial T cells as a way to treat disease, he told STAT.

Choi and Rao’s research points to the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) as controlling the cellular seesaw and therefore the cause of lupus.

AHR activates genes that are important for the birth of IL-22-producing T cells (the good ones in the movie). It also helps suppress CXCL13, a protein that attracts B cells in large numbers. Studies have shown that suppressing AHR leads to the proliferation of harmful cell populations, while boosting AHR with agonists increases the presence of wound-healing T cells. (Studies of joint fluid from patients with rheumatoid arthritis have found a similar phenomenon with CXCL13 and AHR, suggesting that this issue may extend beyond lupus to other autoimmune diseases.)

The researchers ran numerous tests, including using CRISPR to delete the AHR to see what happens, doing single-cell analysis and RNA sequencing, and studying patients undergoing lupus treatment. These experiments were “quite large-scale” and produced “a huge amount of data,” said Marta Alarcón-Riquelme, a professor and scientist at Pfizer Spain and the University of Granada’s Center for Genomic and Oncological Research. The end result is a study that synthesizes many of the abnormalities and imbalances that lupus researchers have reported for decades, offering an idea of the mechanisms by which they occur, she said. (Alarcón-Riquelme was not involved in the study.)

The study also suggests that interferon, a molecule that stimulates the immune system, actively promotes the imbalance by antagonizing the AHR, resulting in even greater inflammation and a decline in beneficial cells. “We’ve known for many years that lupus patients have excess interferon production, but it wasn’t clear how interferon was involved in the disease,” Rao says.

Certain lupus drugs, such as anifrolumab (AstraZeneca’s Safnerol), treat the disorder by blocking interferon. But addressing AHR itself may be a more “surgical” treatment approach, Choi said. For a long time, lupus drugs have broadly suppressed the immune system, which, while effective, can also cause unwanted side effects and health risks.

Clearer insight into the causes of lupus could help drug developers take a more targeted approach, and Rao and Choi’s study “proposes a novel strategy” that focuses on activating the AHR.

Further studies are needed to determine whether IL-22 T cells are indeed beneficial for all lupus patients and have an effect on wound healing, and whether this approach could become a viable treatment for lupus and other autoimmune diseases.

STAT’s coverage of chronic health issues is supported by the following grants: Bloomberg Philanthropies. our Financial Supporters They are not involved in any decisions regarding our journalism.