Mammals are born Oocytes How the cells that a fetus (or egg) needs for the rest of its life stay alive and active for so long is a mystery, but two studies suggest that the answer may lie in the robustness of proteins.

Two studies used traceable isotopes implanted in developing mouse fetuses to measure the lifespan of proteins in the ovaries and found that many of them survive much longer than proteins in other parts of the body. The presence of these “long-lived” molecules, and the support they give to the oocyte and surrounding cells, may explain why. Maintaining fertility.

The first study, led by a team at the Max Planck Institute for Interdisciplinary Sciences in Germany, analyzed oocytes from eight-week-old mice, at which age the animals are in their reproductive prime. Intrauterine It still existed.

The researchers then looked at the older mice to see how long it took for these residual proteins to break down. The answer was, relatively speaking, not very quickly: Some of the proteins remained in the ovaries for most of the mice’s short lives.

“Our data demonstrate that many proteins in oocytes and ovaries are unusually stable, with half-lives that are much longer than those reported in other cell types and organs, such as liver, heart, cartilage, muscle and brain.” write The researchers stated in their published paper:

“The half-lives of many proteins are much longer in the ovary than in other organs, and many more proteins are uniquely long-lived in the ovary.”

A second study, by a team led by US researchers, also found evidence of long-term persistence of ovarian proteins in young mice, including proteins that were present before the mice were born. ZP3were identified for future research.

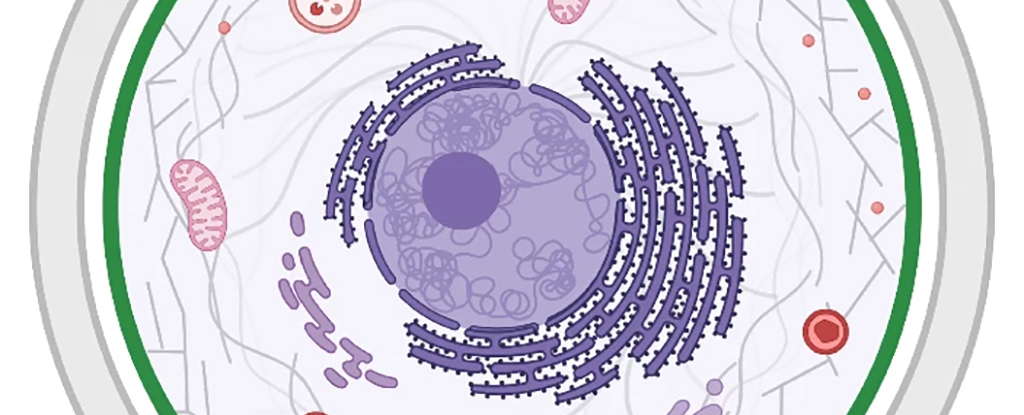

Some of these hardy proteins are Cellular mitochondriaThey are where the cell’s energy is produced. Mitochondria are inherited as part of mammalian egg cells, ensuring that these vital organelles remain functional as they are passed from mother to offspring.

The researchers report that even these proteins, which survive much longer than the norm, eventually fade away and die. The study suggests that this may be related to the natural decline in a woman’s ability to have children, which could eventually lead to ways to treat, or at least better diagnose, infertility.

The findings from the mouse study still need to be replicated in humans, but if successful, they would represent a major advance in our research. Understanding Fertility Learn how to keep your oocytes healthy.

“The extraordinary persistence of these long-lived molecules suggests that they play an important role in the lifelong maintenance of reproductive tissues and their deterioration with age.” write The researchers of the second study wrote in their published paper:

This study Nature Cell Biology and E-Life.