Skenes was making his 11th major league start — his 12th will be Tuesday night in the All-Star Game in Arlington, Texas — and National League manager Torey Lovullo acknowledged that the rookie right-hander is the biggest attraction in the sport right now. Whether he allows 10 hits or not, Skenes is likely to be out in the first inning.

“You’ve got to beat 11, 12 pitchers,” said Lovullo, whose day job is as manager of the Arizona Diamondbacks.

The push and pull facing baseball, made clear during the Midsummer Classic, is common to the Pirates and every organization trying to develop and protect young pitchers: People want to see their best pitchers do more, but teams keep asking them to do less.

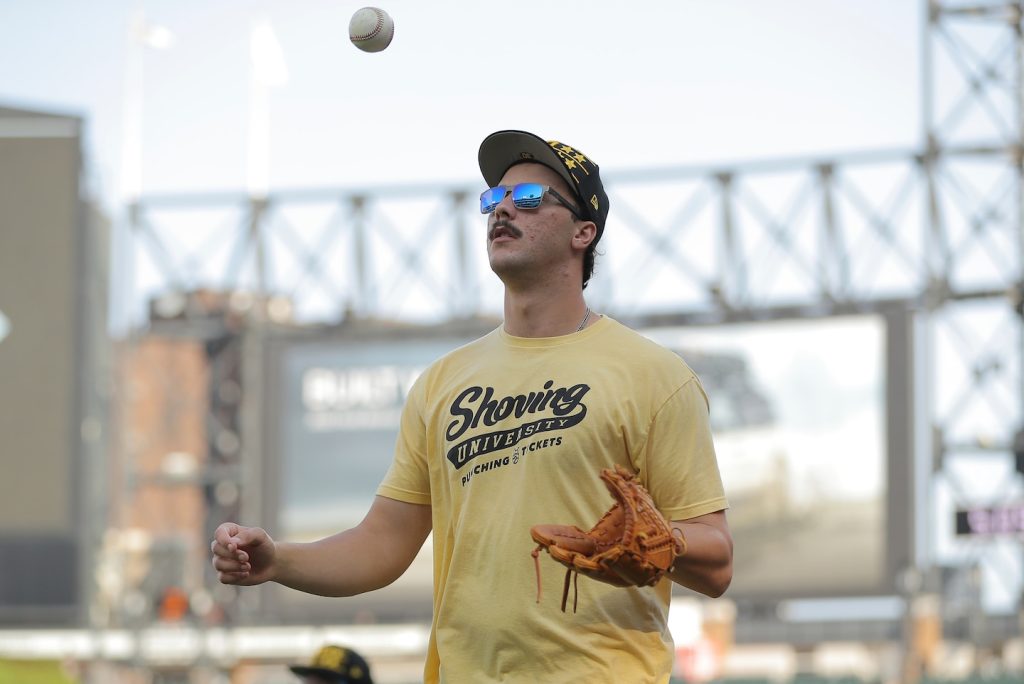

Skenes has been nothing short of phenomenal since being promoted to the Pirates in May. After winning the 2023 Men’s College World Series with Louisiana State University (where he posted an astounding 209-to-20 strikeout-to-walk ratio and allowed 0.75 walks and hits per inning pitched), the Pirates made him their first-round draft pick. His numbers in seven Class AAA starts this spring (0.99 ERA, 0.91 WHIP) earned him a promotion. His performance since then (6-0 with a 1.90 ERA, 0.92 WHIP, 89 strikeouts and 13 walks in 66 1/3 innings) has made him an All-Star.

He was a rising star in a sports world desperate for stars, and Lovullo had a knack for capitalizing on that talent.

“I wanted the world to see him,” Lovullo told reporters in Texas on Monday. “We’re going to be on the biggest stage. [Tuesday]”I’m here to support and promote Major League Baseball in the best way I know how. … He’s a potential generational talent, and I want to give him every opportunity to step on this stage and show what he’s capable of.”

There are limitations, of course, given the exhibition nature of the All-Star Game, but it also defines modern baseball.

Skenes’ most recent appearance came on Thursday at Milwaukee as the starter in MLB’s showcase event. Through the first seven innings, Skenes allowed just one walk and no hits to the Brewers, striking out 11 batters and throwing 99 pitches in a dominant performance.

And Pirates manager Derek Shelton took him out of the game.

“I want to finish the game,” Skenes told reporters in Texas on Monday. “I want to finish what I started, not just in that inning but in every game I pitch.”

That’s a good way to think about a starting pitcher, but it doesn’t reflect the reality of modern baseball.

Sorry to whip an old horse, but the diminished demands on starting pitchers is hurting baseball. This isn’t Shelton’s fault, or the Pirates’ fault, it’s the fault of cold hard facts — starting pitchers are less effective the third time they face a batter than the first — and the sheer terror of front-office people that their most promising young pitchers are almost certain to get injured.

A model employee, Skenes is helping the Pirates get out of a tough spot.

“Obviously, I’m 22 and I think the challenge this year has been just workload management, managing how much I’m playing,” Skenes said, “and, quite frankly, Sheltie, when he was talking to me in the dugout and when he was watching me, he said I looked tired.”

“I felt the same way a little bit. I struggled. I threw over 60 pitches in the first three innings. I think there are games like that. [it] It’s a bit of a shame that it fell to such an outing.”

It’s happened twice before. Skenes was making just his second major league start, pitching six hitless innings against the Chicago Cubs, striking out 11 and walking one, before Shelton benched him in the seventh inning.

That may be smart. But it’s also perverse. Such caution could potentially extend Skenes’ season or career. It certainly robs the sport of much-needed moments.

Great efforts are being made to protect players who play an increasingly smaller role in determining whether a game is won or lost. In the first half of this season, starting pitchers averaged 5.29 innings pitched per game. Last year, it was 5.14. That means 15 or 16 outs, with the final 11 or 12 innings left to full-strength relief pitchers. In the past, most of that work fell on the starting pitchers. As recently as 2011, starting pitchers averaged more than six innings per game. The burden has shifted, and is shifting more.

And cautionary tales are everywhere. The last rookie pitcher to get as much attention as Skenes was Stephen Strasburg. He started his first four games for the Washington Nationals in 2010, striking out 41 and walking five. In his 12th start at Philadelphia in August, he shook up his right arm and was replaced in the fifth inning. He had Tommy John ligament replacement surgery in his elbow. He didn’t pitch in the major leagues again until the following September.

The next year, the Nationals managed Strasburg’s innings and took him out of the rotation even as Washington made the playoffs. It was brazen then, but it’s more common now. Skenes threw 129⅓ innings last year in college and the minor leagues combined, but he’s never thrown more than that. He’s already up to 93⅔ innings this season. The baseball industry closely monitors these numbers. The Pirates, just 1.5 games out of the NL wild-card spot, could be facing a Strasburg-like problem.

But there’s no surefire way. Teams continue to monitor pitchers. Pitchers continue to have elbow problems. Let’s hope that Skenes is different. That was the case for his first 11 starts.

“Hopefully I’ll get more time to play this game,” Skenes said.

Pray and hold your breath. What’s best for the sports world is for Skenes to remain an anomaly and stay healthy, because he’s the magnetism that sells tickets and gets the attention of the crowd. What’s best for the Pirates might be for him to single in the first or second inning every game, so that when Shelton does what he feels is his duty, he doesn’t rob Skenes, or any of us, of the moments he could have had.