Moods and emotions play an important role in our daily lives. They affect how we experience things. For example, whether we start our day feeling hopeful and energetic or grumpy and lethargic. Moods and emotions influence whether we interpret events positively or negatively.

But people with bipolar disorder experience rapid and unpredictable mood swings that can lead to “swings” of low and high moods, with potentially serious consequences, though researchers don’t know exactly what causes these extreme mood changes.

Now, in our new study, Published in Global Open Science in BiopsychiatryWe have uncovered the brain regions that control mood and how the brain responds to pleasure in bipolar disorder. Our findings may one day lead to better treatments.

We experience mood changes throughout the day. When we are in a good mood, we tend to see things more favorably. Our good mood as well And it gains momentum.

Similarly, when you’re in a bad mood, you tend to perceive a bad outcome as even worse than it actually is, and this negative mood can gain momentum and make you feel worse as well.

This momentum of mood can bias the way you perceive events and the decisions you make. Imagine going to a new restaurant for the first time. If you happen to be in a great mood, you may perceive the experience as much better than it actually was. This creates an expectation that your next visit will have a similarly good experience, leading to disappointment when it doesn’t.

The process by which mood biases the perception of pleasant or rewarding experiences has been thought to be amplified in people with bipolar disorder, whose moods can quickly become extreme.

Previous research has shown that these extreme mood cycles It may be caused From life experiences that involve important goals, such as doing well on an exam, buying a property, getting promoted, etc. This may or may not lead to you achieving your goal.

Bipolar disorder has been described by people who experience it as: A double-edged swordMany people with bipolar disorder vigorously pursue, and often succeed at, goals that are important to them, alongside periods of manic (mild) or depressive mood swings.

But what happens in the brain when our mood changes instantaneously in response to a pleasurable experience?

Brain mood swings

Pleasurable or rewarding experiences activate specific circuits in the brain and activate substances called neurochemicals. DopamineThis helps them learn that the experience was a positive one and that they should repeat the behavior that created this enjoyable experience.

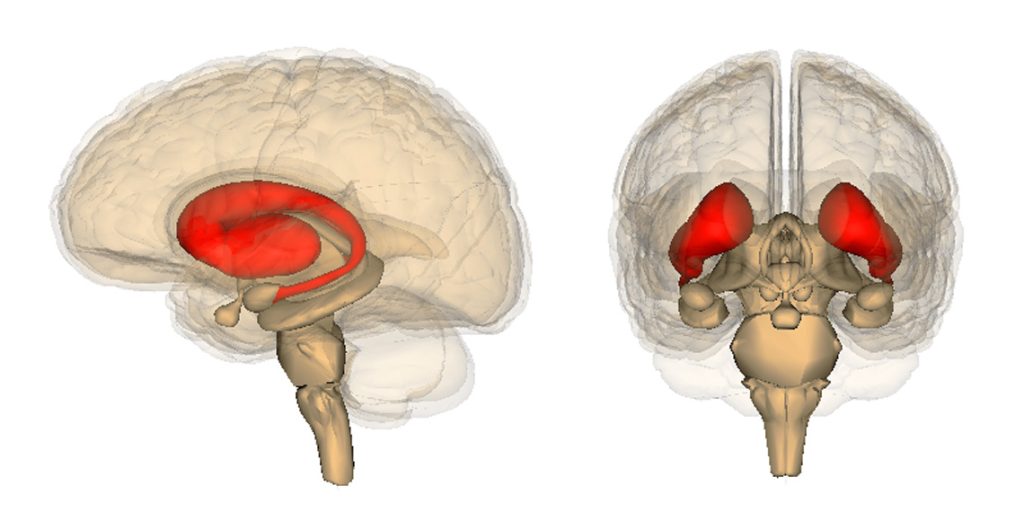

One way to measure the brain’s response to reward is to Ventral striatum – A key area of the reward system that controls pleasure.

The aim of our study was to investigate what happens in the ventral striatum during momentary mood changes in 21 subjects with bipolar disorder and 21 control subjects. We wanted to measure this down to the second in response to monetary reward.

While placed in a brain scanner, participants were asked to play computer games in which they could win or lose real-money bets. To determine which parts of the participants’ brains were active, blood flow was measured using a technique called functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

They also used mathematical models to calculate participants’ mood “momentum” – how good they would feel if they continued to win.

In all participants, the brain regions involved in the experience and recognition of temporary mood states Anterior insula.

However, during periods of upward momentum, when participants won multiple times, the ventral striatum showed strong positive signals only in participants with bipolar disorder, meaning that they experienced a heightened sense of reward.

They also found that participants with bipolar disorder had reduced communication between the ventral striatum and the anterior insula, whereas in controls, both regions fired in an integrated manner.

This suggests that control participants were more aware of their mood when recognizing rewards in the task. Although participants may have found winning rewarding, they may have been more aware of how good winning made them feel. This may help participants adapt quickly to changing circumstances (for better or worse) and prevent overinflated expectations of getting future rewards.

But the opposite was true for participants with bipolar disorder: They were less able to distinguish between how exciting or pleasurable a reward was and their own mood.

These findings may help explain why people with bipolar disorder get caught in a vicious cycle of worsening moods and sometimes taking greater risks than usual.

The same mechanisms that cause positive moods can also cause negative mood cycles. An unexpected loss during a winning streak could shift mood into a negative cycle, leading to negative expectations and corresponding changes in behavior. However, future studies should investigate negative mood cycles more specifically.

Our findings may also be useful in developing interventions to help bipolar disorder patients better dissociate mood from perception and decision-making without attenuating stimulating experiences. Since dopamine neurons are tightly connected to the ventral striatum, it will be interesting to see whether dopamine drugs can improve this mood bias.![]()

![]()

This article is reprinted from conversation Published under a Creative Commons license. Original Article.