Bo Barker-Jorgensen, a marine biogeochemistry expert who was not involved in the study but reviewed it, said in an interview that it was a “very unusual discovery.”

The discovery could have implications for the deep-sea mining industry, which is seeking permission to explore the ocean’s depths and extract minerals such as those that make up polymetallic nodules. It is seen as essential to the transition to green energy by environmentalists and many scientist believe Deep sea mining is dangerous “The oceans are a very important part of our ocean ecosystems, and we need to be aware of how they are affected by climate change,” said Dr. Gregory B. Schneider, a professor of oceanography at the University of California, Berkeley.

Andrew Sweetman, the study’s lead author, said that when he first recorded unusual oxygen levels on the Pacific ocean floor in 2013, he thought his lab equipment had malfunctioned.

“I told the students to put the sensors back in the box and send them back to the manufacturer to be tested, because they were giving us nonsense,” says Sweetman, who is head of the Submarine Ecology and Biogeochemistry Research Group at the Scottish Institute for Marine Science. He told CNN“And every time the manufacturer said, ‘It’s working fine. We’ve adjusted it.'”

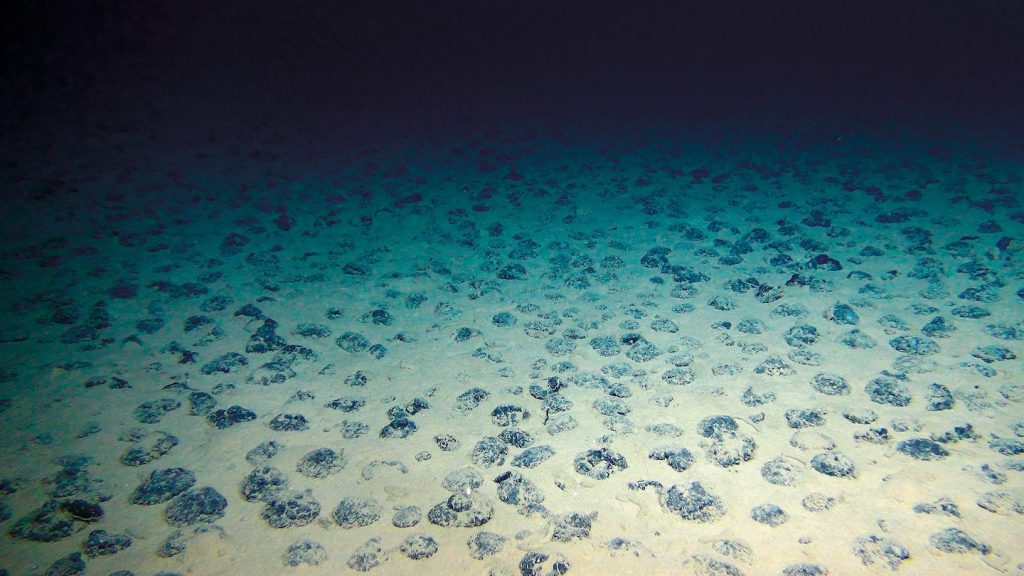

In 2021 and 2022, Sweetman and his team returned to the Clarion-Clipperton area, an area of the central Pacific Ocean known for its abundance of polymetallic nodules. Confident that the sensor worked, they lowered it more than 13,000 feet below the ocean’s surface and placed a small box in the sediment. The box remained there for 47 hours, conducting experiments and measuring the oxygen levels consumed by the microorganisms living there.

Instead of decreasing, oxygen levels are increasing, suggesting that more oxygen is being produced than is being consumed.

The researchers found that the electrochemical activity of the various metals that make up the polymetallic nodules is In an interview, Tobias Hahn, one of the study’s co-authors, said the oxygen production measured by the sensor acts like a battery, where electrons flow from one electrode to the other to create an electric current.

The hypothesis adds a new dimension to our understanding of how life on the ocean floor came to exist, said Hahn, who paid particular attention to the sensors used in the research experiment. “We thought that photosynthesis started, and that photosynthesis brought oxygen to Earth, and that’s how life began on Earth. In fact, this process of electrochemically splitting water into oxygen and hydrogen may have provided oxygen to the oceans,” he said.

“This could be something of a game-changer in the story of how life began,” he added.

a Research news release The findings call into question “the long-held assumption that only photosynthetic organisms such as plants and algae produce oxygen on Earth,” the researchers said.

But if the findings are confirmed, “we will need to rethink how we mine materials such as cobalt, nickel, copper, lithium and manganese from the ocean so as not to deplete oxygen sources for deep-sea organisms,” Franz Geiger, a chemistry professor at Northwestern University and one of the study’s co-authors, said in a statement.

Undersea mining in the 1980s offers a lesson, Geiger says: When marine biologists visited those sites decades later, “we found that even bacteria hadn’t recovered.” But in areas that weren’t mined, “marine life thrived.”

“We still don’t know why these ‘dead zones’ persist for decades,” he says, but the fact that they persist suggests that seafloor mining in areas with lots of polymetallic nodules could be particularly harmful because those areas tend to have higher faunal diversity than “the most diverse tropical rainforests,” he says.

While the study points to an intriguing new pathway for supporting life deep in the ocean, Hahn said many questions remain: “We just don’t know how much ‘dark oxygen’ is produced by this process, what effect it has on the polymetallic nodules, or how many nodules are needed to allow oxygen production,” he said.

While the research methods are solid, “we’re still missing an understanding of what’s going on and what the process is,” Barker-Jorgensen said.