COVID-19 was once Cough for 2 weeks and I can’t figure out the scent of my new candleAnd we Long COVID – Vague collection Over 200 Symptoms It can be debilitating, even months or years after the original illness appears to have been cured.

Four years into the pandemic, we still don’t fully understand what causes this prolonged illness, but a new study that followed 24 COVID-19 patients for up to 900 days has uncovered a previously unnoticed potential contributing factor: T cells.

the Not the first study What links COVID-19 to these specific immune cells? last monthA study from Imperial College London has hinted at the potential of targeted T-cell therapy to fight the disease, but it’s one of the longest-running studies, having been launched in 2020, long before the idea that COVID-19 could persist in the body was widely accepted.

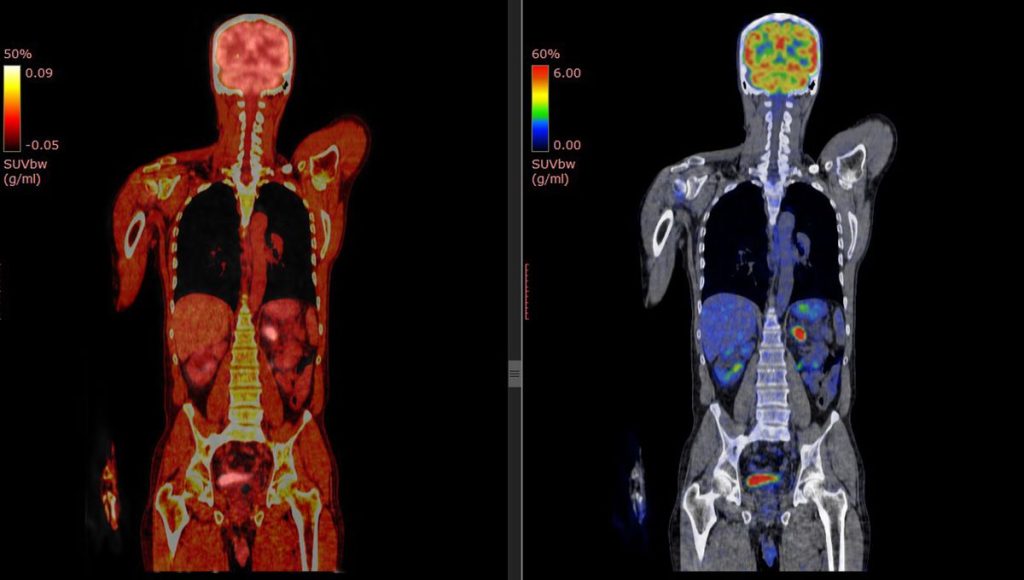

But that’s not all that’s special: the team was inspired by their experience studying HIV, the AIDS virus. Substantially defined the T-cell killing abilityBecause it wasn’t possible to monitor antibodies early in the pandemic, researchers instead used PET scans to study the behavior of T cells in the body after infection.

“[It] It’s a novel approach […] This makes it possible to map activated T cells in the body.” explanation Danny Altman, professor of immunology at Imperial College London, co-author of the Penguin Handbook of Long COVID and principal investigator of the NIHR WILCO LONG COVID study, who was not involved in the research.

“The researchers found patterns of T cell activation over time that may help explain patterns of long-term COVID symptoms,” he said. “For example, people with respiratory symptoms were shown to have activated T cells that persist in the lungs for a long time.”

Other scans showed activated T cells swarming the intestinal wall, leading the team to analyze intestinal biopsies, where they again found the presence of COVID-19 RNA, a “long-term viral reservoir,” Altman explained.

The finding is even more striking when compared with six control samples from before the pandemic, when “no one on the planet could have been infected with this virus,” said Michael Peluso, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco and lead author of the paper. statisticsThese scans showed that T cells were activated, but as expected, they were concentrated in the liver, kidneys and other areas known to help clear inflammation. In long-covid patients, T cells were everywhere.

“It’s really mind-blowing,” Peluso said. “‘Oh my goodness, this is happening in people’s spinal cords, in their digestive tracts, in the walls of their hearts, in their lungs.'”

The study isn’t conclusive: It’s not actually clear what the T cells are responding to, and the researchers aren’t sure whether the scans show remnants of an old infection or active virus particles. Still, the work is intriguing. “There’s a large amount of inferential data to support the view that the inability of some people to properly clear the virus and harbor reservoirs of SARS-CoV-2 in their tissues is an important driver of long Covid,” Altman notes, but “that’s hard to prove.”

In that respect, he said, the study “should be seen as an important step in improving our understanding of the process of this disease, thereby bringing us closer to a treatment that could offer hope to tens of millions of patients.”

“At a time when new clinical trials are desperately needed, studies like this one help show the way.”

The study has been published in the journal Science Translational Medicine.