If you have seen Predatoryou realize that heat vision gave the alien warriors a tactical advantage – indeed, it put Dutch and his squad in a position of being pursued, despite their otherwise well-camouflaged condition.

But back to reality, it seems that the prey has the ability to sense the infrared spectrum. Research has shown that this unique ability is all on the hairs on the backs of the smallest mammals.

Don’t rely on the hair on my back

Small mammals like shrews and rodents have fur, a thick, protective layer of multiple types of hair. This fur should keep the animal warm, relatively dry, and protect it from the environment. But what if it could also protect them from predators? Within this fur are special “guard hairs” that researchers think act as fine-tuned infrared sensors.

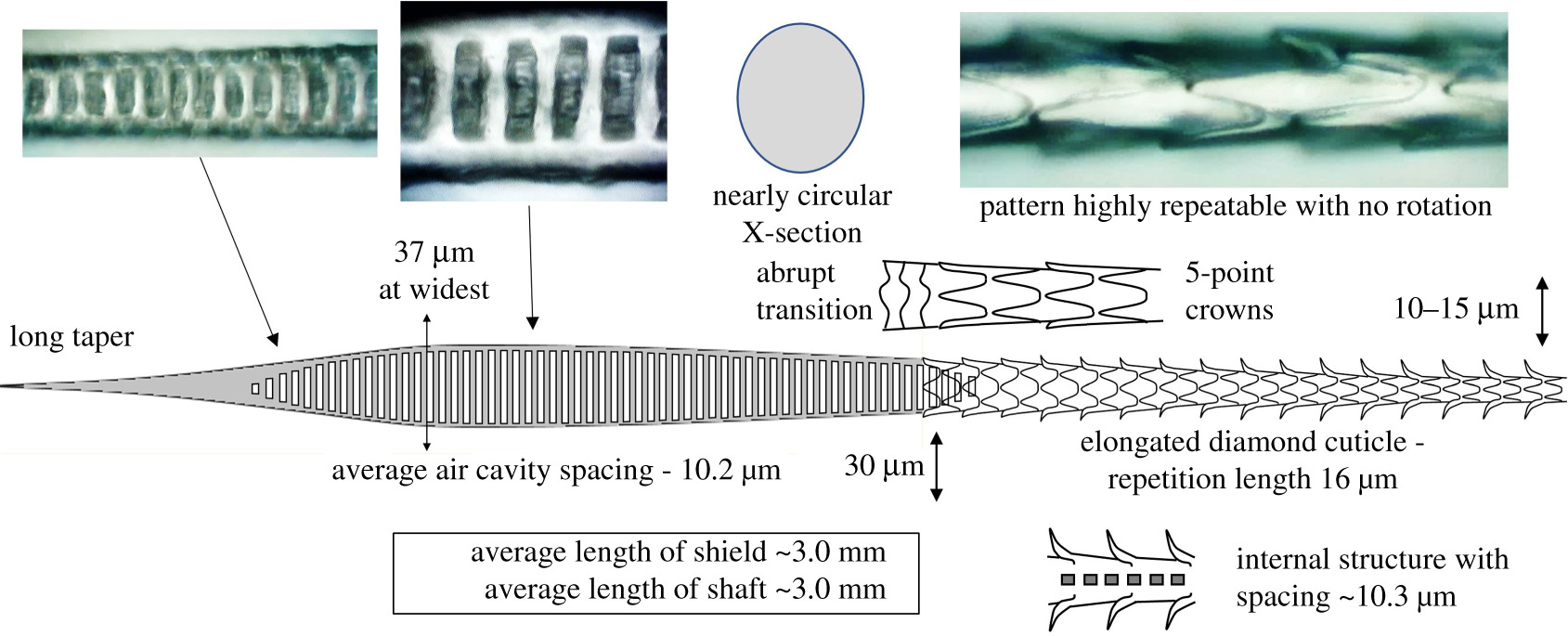

Guard hairs make up only 1-3% of the fur. They usually stick out straight and protrude somewhat from the rest of the fur, and tend to feature a fairly distinctive striped pattern not seen in other types of mammalian hair.

The periodic stripes found in the guard hairs of small mammals have puzzled scientists for years. These hairs have internal stripes spaced 6 to 12 micrometers apart. If you’ve peered closely at a graph of the electromagnetic spectrum lately, you might have noticed a close match with infrared wavelengths. This suggested an unrecognized capability, perhaps the ability to sense infrared light. In fact, these wavelengths cover the same part of the infrared spectrum used by heat-seeking missiles and thermal imagers.

This is an obvious survival advantage for nocturnal, predatory animals: it can give small creatures the ability to sense warm sources of heat, such as a predator approaching from behind, without them having to have eyes in the back of their head or constantly looking over their shoulder. When their heat sense detects something warm approaching from behind, it might be worth performing a dash action.

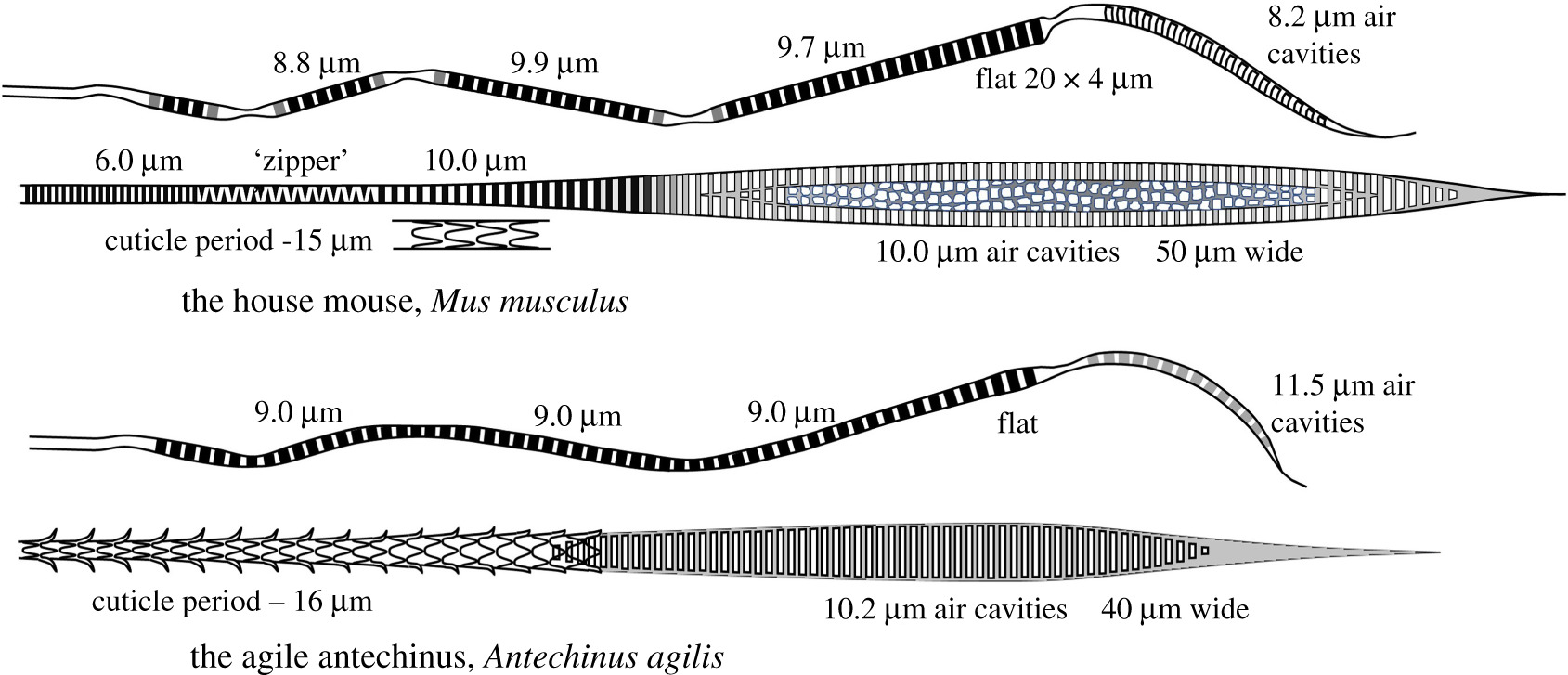

The researchers focused their study on three fur species: House mouseHe is a house mouse. Antechinus agilis, mouse-like marsupials, and Solex araneusDespite the many differences between the different species, their guard hairs share some similarities. Their findings show that despite evolutionary divergence stretching back millions of years, these species share very similar microscopic hair structures that appear to be tuned to wavelengths between 8 and 12 μm, which are ideal for thermal imaging.

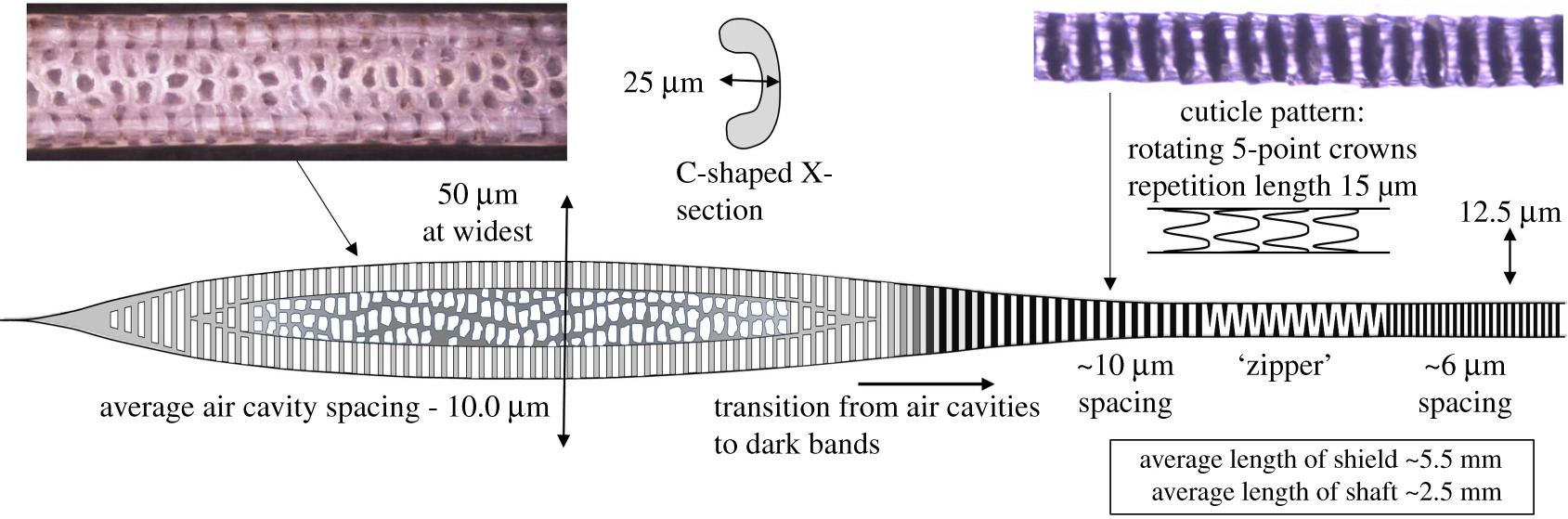

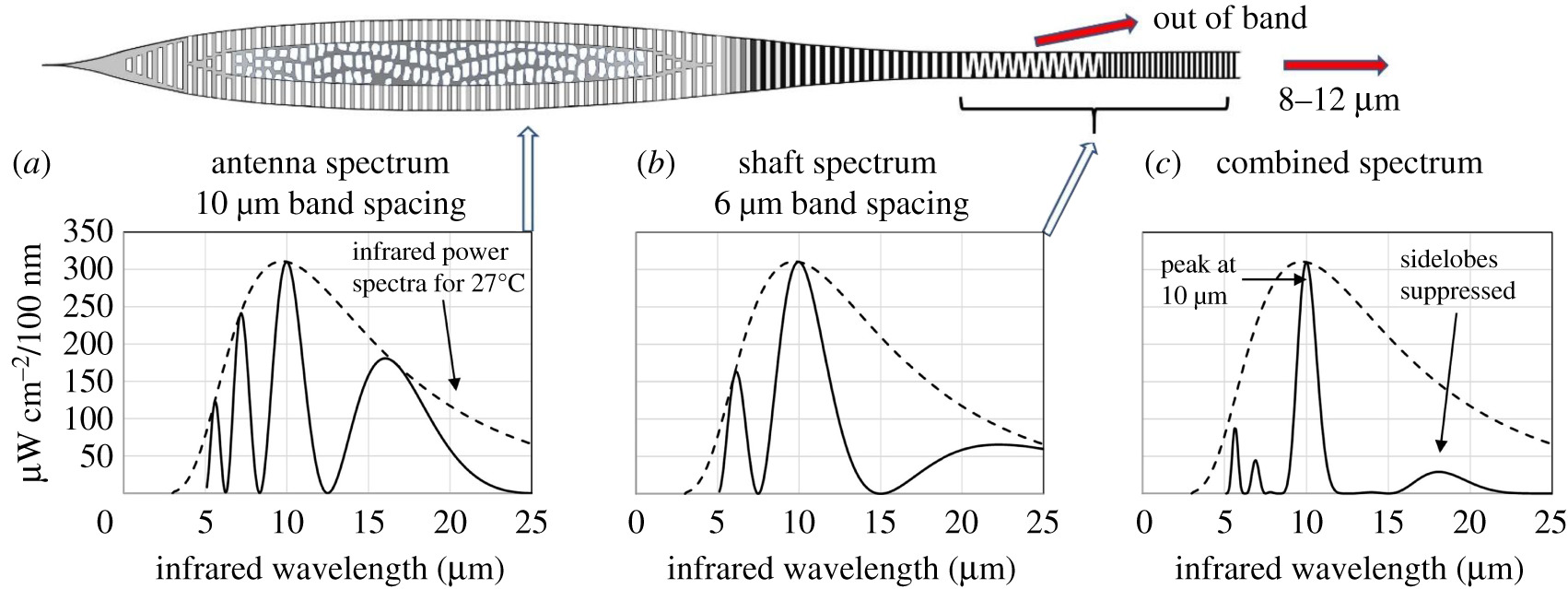

Taking the mouse as a prime example, the hairs have a sophisticated structure. The wider section of the guard hair is called the “shield” and is thought to act as an infrared absorber. It is essentially two tubes connected by a membrane, with cavities spaced about 10 microns apart. Towards the base of the shield region the hair tapers, and instead of cavities the hair has characteristic dark bands at similar intervals. The narrower section is thought to help concentrate the absorbed infrared energy to the base of the hair. This is followed by a relatively variable “zipper” section, with dark hemispheres arranged around the shaft of the hair. This is thought to act as a “spectral filter” that emits wavelengths outside the 8-12 micron band. Calculations suggest that the zipper filter allows infrared energy in that critical wavelength range to make up 72% of the “signal” that reaches the base of the hair, and only 33% elsewhere. The final section of the shaft has finer stripes spaced only 6 um apart.

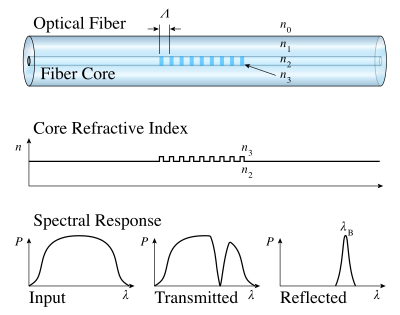

The hairs are thought to act similarly to infrared antennas; their stiff, straight arrangement and periodic striped pattern allow them to act as heat detectors. The stripes themselves appear to be made of infrared-transparent biological material with different refractive indices. The researchers liken this to a man-made invention called a fiber Bragg grating (FBG), which uses periodic changes in the refractive index of optical fibers to create filters for specific wavelengths. Using a biological version of the same mechanism, guard hairs are able to filter out infrared wavelengths of interest.

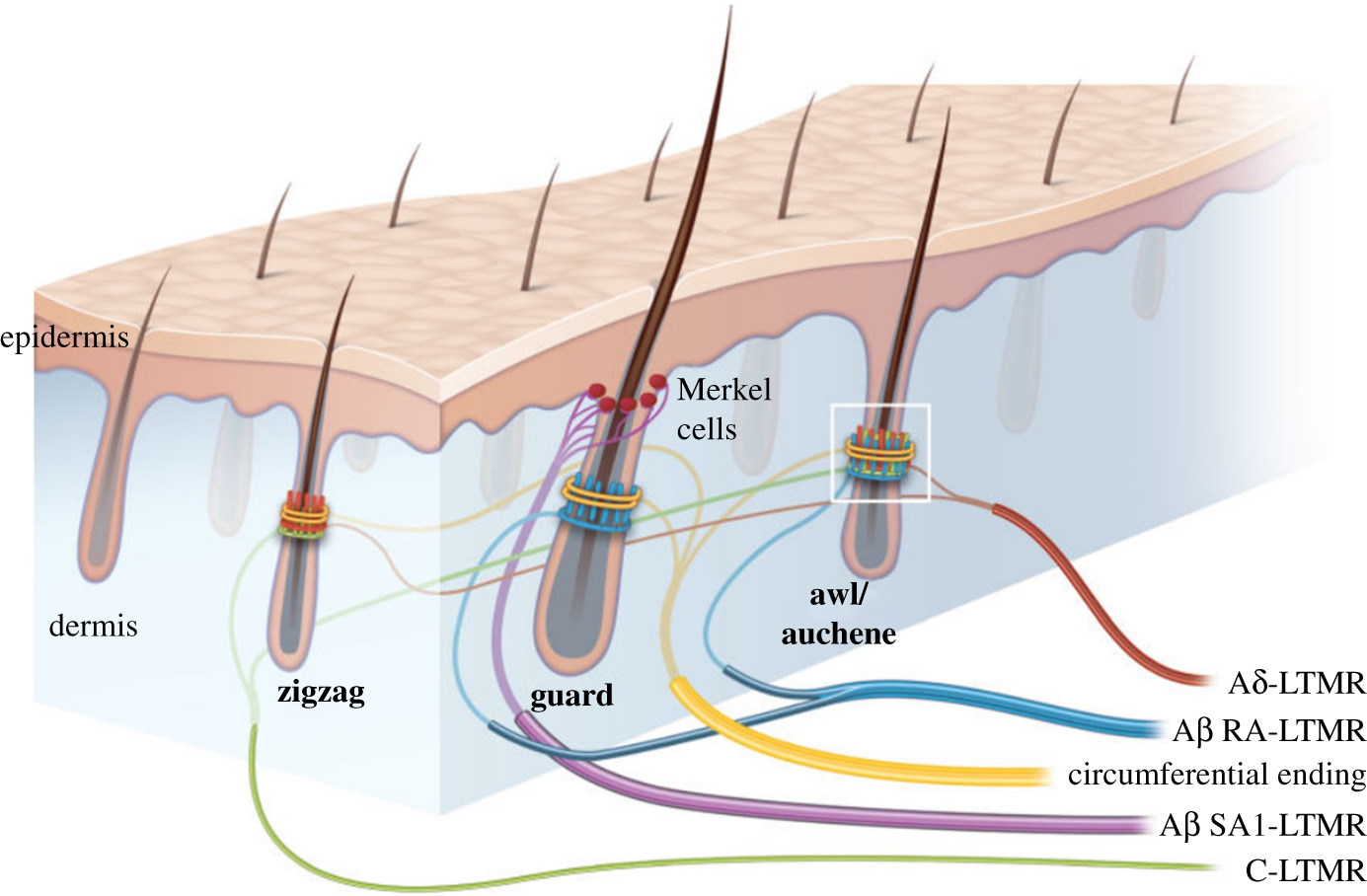

On the other hand, to pick up the signal, the animal needs some kind of sensor cell at the base of the hair. In fact, the researchers found that mice have Merkel cells that are uniquely positioned at the base of their hair, arranged around the hair shaft. It is thought that these cells are responsible for the actual infrared sensing, and the hair itself just acts as an antenna to focus the infrared energy.

The researchers then expanded their study to see whether predators had adapted to this. In particular, they found that cold-blooded snakes are practically invisible in the infrared heat range. Similarly, cats have relatively low frontal thermal radiation. Thus, both have an advantage in hunting mammals that have a heat-sensing defense mechanism. And indeed, these creatures are particularly adept at hunting mice and other small mammals. This is not surprising.

Research is still in its early stages; more studies are needed to confirm the true purpose of these guard hairs. Either way, their complex microscopic structure provides compelling evidence that the guard hairs do in fact function as antennae to capture infrared light for sensory purposes.

The discovery of these natural infrared sensors is not just a biological curiosity. It could also be useful in the field of photonics: the ability of guard hairs to act as fine-tuned infrared antennas could inspire new optical instruments or improve current technology.

Furthermore, the study could have implications for evolutionary biology, providing new insights into the ancient origins of hair in mammals and marsupials: the durability of guard hairs over millions of years suggests that they played an important role in the survival of early mammals, possibly dating back to the Triassic period.

Either way, certain small mammals have always had the ability to deftly dodge predators sneaking up on them from behind, and now we may have a secret insight into this little party trick. Perhaps it’s not their eyes or their keen vibration sense, but a hidden temperature sense that’s been lurking in their fur all this time.

Featured Image: “Lab Mouse mg 3263” by [Rama]