Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore space with news of fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

CNN

—

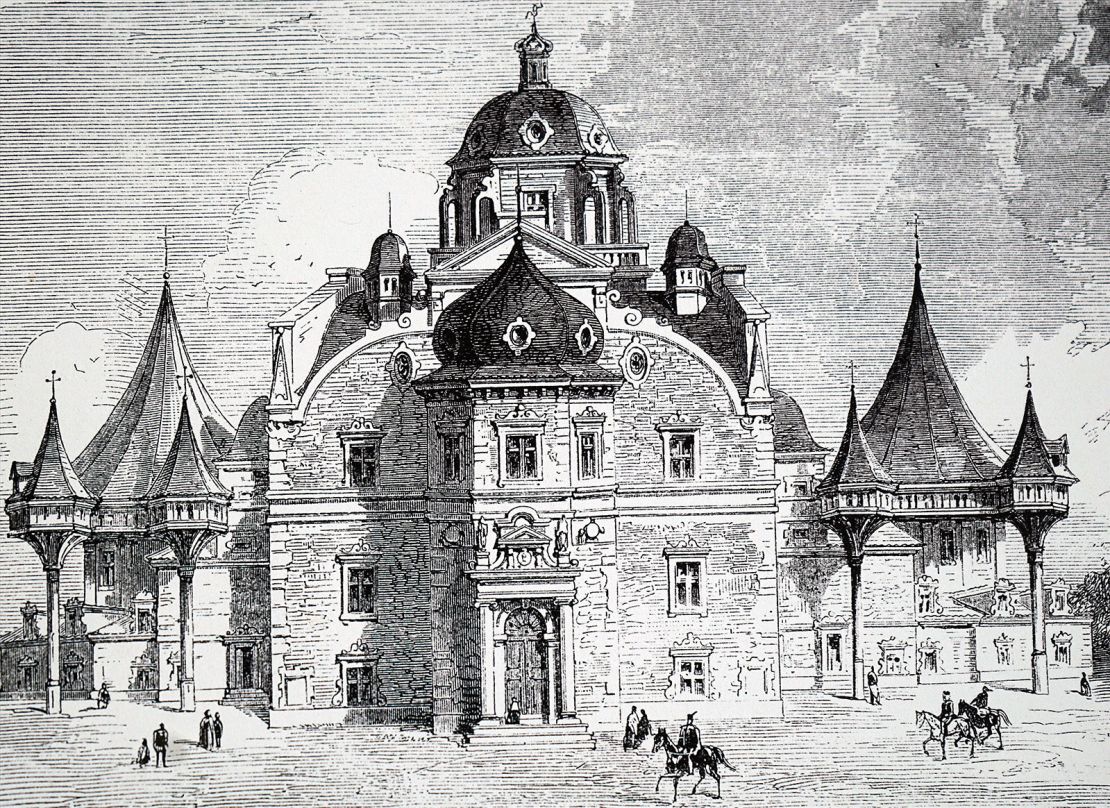

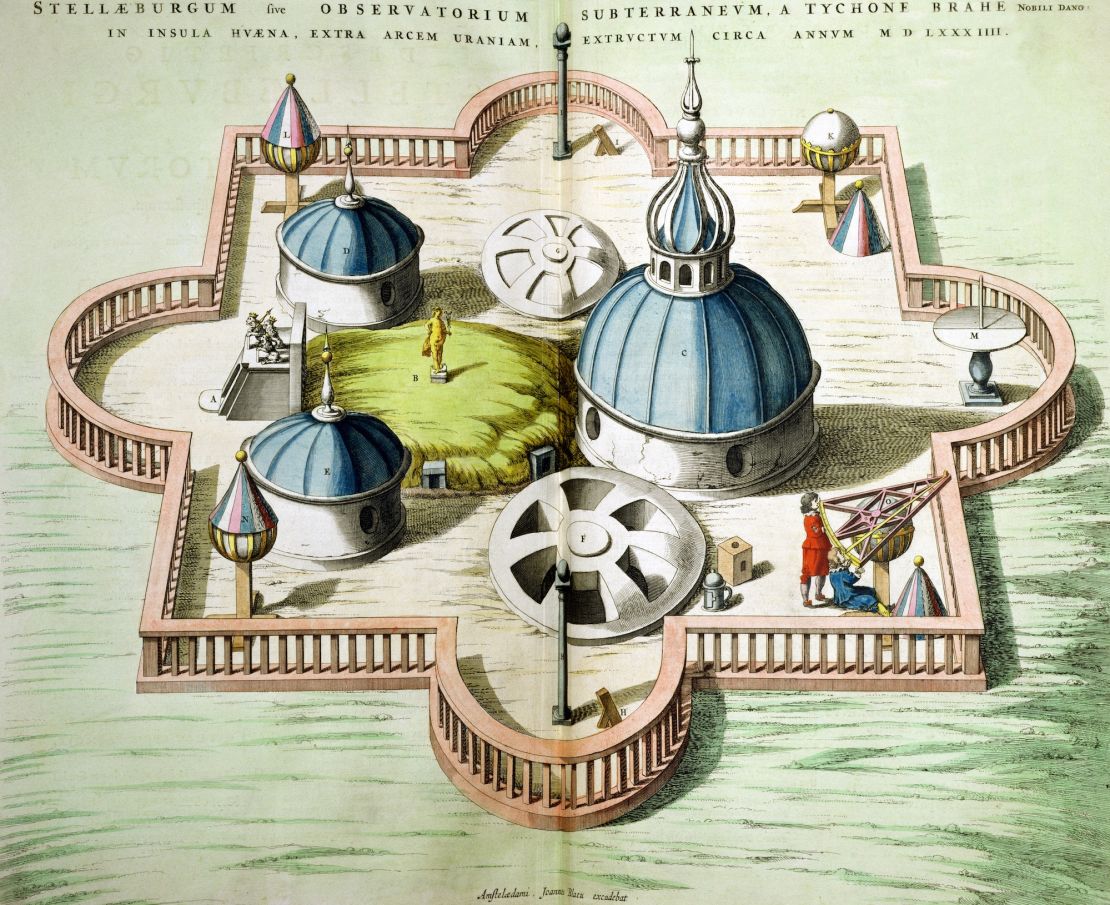

Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe is best known for his celestial discoveries made in the 16th century before the invention of the telescope, but he was also an alchemist who concocted secret potions for his upper-class clients. But what Brahe actually worked on in his alchemical laboratory beneath the castle residence and observatory called Uraniborg has been something of a historical mystery.

Brahe’s work was conducted in secrecy, as was common among Renaissance alchemists who kept their knowledge secret. Today, only a few of his alchemical recipes remain. Uraniborg, named after Urania, the muse of astronomy, on the island of Vän off the coast of Sweden, was demolished after Brahe’s death in 1601.

Now, researchers conducting chemical analysis of glass and ceramic shards recovered from the site where the Uraniborg once stood say they have uncovered new clues about what went on in the Renaissance scientist’s laboratory centuries ago.

The five fragments studied in the new study were: Another team conducted excavations between 1988 and 1992. Fragments found in the remains of the gardens surrounding the site are thought to have come from an alchemy laboratory.

Kare Lund Rasmussen, professor emeritus at the Department of Physics, Chemistry and Medicine at the University of Southern Denmark, came up with the idea for the study after wondering what insight the fragments could provide into understanding Brahe’s work on alchemy.

“Four of the fragments contained higher than expected concentrations of elements, including nickel, copper, zinc, tin, mercury, gold and lead,” the researchers reported in the journal Nature on Wednesday. Heritage Science.

Gold is one of the materials that Rasmussen had already associated with Brahe. In his continuing efforts to understand why Renaissance scientists died, Rasmussen Survey conducted in November 2016 Analysis of some of Brahe’s hair and bones revealed large amounts of gold in his remains.

But the biggest revelation from the glass and pottery shards uncovered in the new analysis, and another source of mystery, is the presence of elements unknown even to scientists in Brahe’s time.

Rasmussen and his team were surprised to find tungsten among the elements they found inside and outside the fragment. Mercury and gold were commonly used in Renaissance formulas to treat a variety of ailments, but the evidence for tungsten in them was “very puzzling,” he said.

“What are we to infer from the fact that tungsten hadn’t even been described at the time, yet there were traces of it in the debris from Tycho Brahe’s alchemy studio?” Rasmussen says.

Swedish chemist Karl Wilhelm Scheele In 1781, more than 180 years after Brahe’s death, tungstic acid was discovered in the mineral now known as barite. Shortly thereafter, Spanish chemists Juan José and Fausto Delhual and de Suvisa He then carried out additional experiments that successfully isolated tungsten, as described in a paper published in 1783. Tungsten, also known as wolfram, occurs naturally in certain minerals.

Rasmussen said the tungsten could have found its way to Brahe’s lab through minerals, or that Brahe could have processed the minerals in a way that isolated the tungsten without his knowledge.

Brahe may have also come across tungsten through the work of German mineralogist George Agricola, who, while attempting to smelt tin from tin ore, discovered the formation of an unusual substance that he named Wolfram in his 1546 book On the Nature of Fossils.

“Maybe Tycho Brahe heard about this and knew about the presence of tungsten,” Rasmussen says, “but this is not something we know, or can say based on the analysis I’ve done. This is simply a possible theoretical explanation for why tungsten is in the sample.”

The new findings will be of interest to historians and archaeologists, said Lawrence Principe, the Drew Professor of Humanities at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and director of the university’s Singleton Center for Premodern European Studies, who was not involved in the work.

“As the authors point out, the discovery of tungsten residues is quite surprising,” Principe said. “Tungsten ores are relatively rare, and little is known about the extent to which they were experimented with in the early modern period.”

Principe believes that anyone who encountered tungsten ore would have been struck by its extreme weight – the element’s name means “heavy stone” in Swedish – “so they might have tried to smelt it for gold, and I suspect that’s exactly what happened here,” he said.

Astronomer and Alchemist

Brahe was a dynamic Renaissance scientist who rose to fame after discovering the supernova in 1572. Brahe was so highly regarded that King Frederick II of Denmark and Norway offered him the island of Vän as a place to build an astronomical observatory and alchemical laboratory. The estate served as a residence and scientific research center where students from all over Europe came to live and study, and the underground alchemical laboratory contained several specialized furnaces, according to the research paper.

The laboratory was unique in design, with 16 furnaces for heating, ash production, and distillation, and copper piping running outdoors for cooling. A spiral staircase led to the family living room, known as the “winter room,” so Brahe was never far from the laboratory.

Rasmussen believes that the reason the king gave such generous gifts to Brahe was not only because of the good relationship between them, but also because European kings were more highly regarded if they kept famous scientists in their own countries and did not want to lose them to other countries, and Brahe himself wrote that the king was keen to support the scientist’s work in both astronomy and alchemy.

Alchemy, the precursor to chemistry, had two aims: to produce gold and to make medicines. Focused on producing gold, alchemists tried to create it through experimentation from less valuable metals and minerals.

Brahe was inspired by the German physician Paracelsus to focus his time and energy on creating medicines rather than gold. Diseases like the plague, leprosy and syphilis were rampant at the time, so alchemists like Brahe focused on concocting medicines to treat those ailments, along with fevers and stomach aches, Rasmussen said.

“Today we might be a little skeptical about the efficacy of Paracelsian medicine in the late 1500s, but it was high tech and cutting edge at the time,” Rasmussen said.

Brahe shared his secret recipes with only a few people, including his patron, Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, who reportedly asked him for a cure for the plague.

Brahe’s plague cure was complex and included theriak (a treatment used at the time for a variety of illnesses) which contained up to 60 different ingredients, including opium, snake meat, oils, herbs and sulphates. Brahe’s plague cure also contained precious tinctures of hyacinth, coral, sapphire and drinkable gold.

Given the amount of gold found on Brahe’s body, it is possible that he also took potions containing drinkable gold.

While the new findings raise more questions than they answer about Brahe’s alchemical work, Rasmussen said he hopes to analyze a large number of new samples from the alchemy lab in the future to find more clues.

It may seem odd that an astronomer who developed sophisticated instruments to observe the heavens and map the positions of more than 700 stars would be involved with alchemy, but it all comes back to Brahe’s worldview, said study co-author Grinder Hansen.

“He believed there was a clear connection between celestial bodies, earthly substances and the organs of the body,” Grinder Hansen said in a statement. “Thus the sun, gold and heart were connected, and the same was true for the moon, silver and brain. Jupiter, tin, liver, Venus, copper, kidneys, Saturn, lead, spleen, Mars, iron and the gallbladder, as well as Mercury, mercury and the lungs. Minerals and gemstones were also linked to this system; the emerald, for example, belonged to Mercury.”

Principe, the science historian at Johns Hopkins University, said Brahe and British physicist and mathematician Isaac Newton were some of the leading figures of the scientific revolution who worked with alchemy.

“Contrary to popular objections against alchemy from the 18th century onwards, alchemy and chemistry are not different in practice, and anyone seriously interested in substances and their transformations, and especially with a desire to control those transformations in order to produce objects, would naturally have engaged in alchemy,” he said.

After Frederick II’s death, Brahe and the new king, Christian IV, did not have a good relationship. Brahe was known to ignore the king’s orders, including those to keep the fire burning at the Klann lighthouse in southwest Sweden and to keep the chapel that housed the remains of the king’s mother and father, Rasmussen said. So when Brahe died in 1601, the king and his advisers had Uraniborg destroyed, so it could no longer stand as a memorial to the scientist, and the bricks were reused in other buildings.

However, Brahe’s scientific achievements have not been forgotten. He is recognized for the great advances he made throughout his lifetime, and his groundbreaking work paved the way for future scientists.

Brahe correctly believed that the Moon orbited the Earth and the planets orbited the Sun, but he also thought that the Sun must orbit the Earth, but it was his assistant, Johannes Kepler, who developed the laws of planetary motion to understand how the planets orbit the Sun.

Brahe, Kepler, Newton and Galileo Galilei changed the way people understood the world and their place in the universe.

“Tycho Brahe was the first of four giants who stood on each other’s shoulders, 25 years apart, between 1580 and 1680, and who shaped our so-called modern world view as opposed to the medieval one,” Rasmussen said.