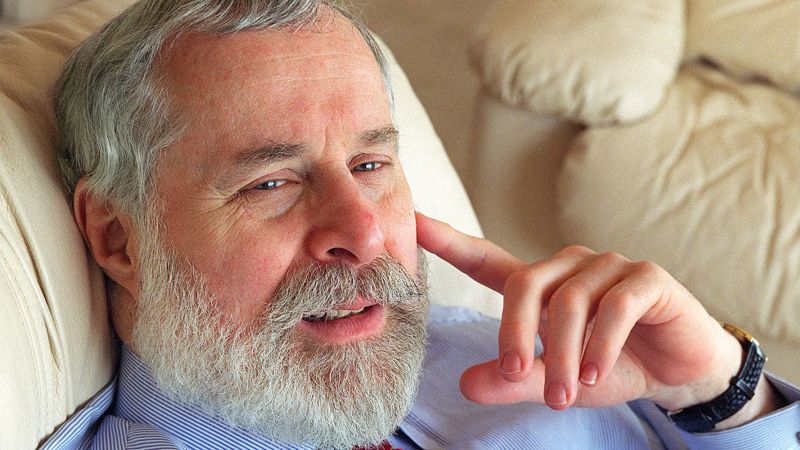

NEW YORK (AP) Peter Buxton, the whistleblower whose work known as the Tuskegee Study exposed how the US government denied hundreds of black men in rural Alabama treatment for syphilis, has died. He was 86 years old.

Buxton died of Alzheimer’s disease on May 18 in Rocklin, California, according to his lawyer, Minna Farnan.

Buxton is revered as a hero among public health scholars and ethicists for bringing the phenomenon to light. The most infamous medical research scandals It was the largest study in U.S. history. The documents Buxton provided to the Associated Press, and subsequent investigations and reporting, led to an outcry and the study was closed in 1972.

Forty years ago, in 1932, federal scientists began studying 400 black men with syphilis in Tuskegee, Alabama. When antibiotics that could treat the disease became available in the 1940s, federal health officials ordered the drug supply withheld. The study looked at how the disease affected the body over time.

While working as a federal public health officer in San Francisco in the mid-1960s, Buxton overheard colleagues discussing the study. The research wasn’t a secret: About a dozen medical journal articles about it had been published over the previous 20 years. But few people expressed concerns about the way the experiments were conducted.

“This study was fully accepted by the American medical community,” Ted Pestorius of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said at a 2022 program marking the 50th anniversary of the study’s completion.

Buxton’s reaction was different. After learning more about the study, he expressed ethical concerns in a letter to CDC officials in 1966. In 1967, he was summoned to a meeting in Atlanta, where CDC officials accused him of disrespect. Repeatedly, CDC leaders rejected his complaints and his requests to treat the Tuskegee men.

He left the U.S. Public Health Service to attend law school, but the study haunted him. In 1972, he provided documents about the study to Associated Press reporter Edith Lederer, whom he met in San Francisco. Lederer passed the documents on to AP investigative reporter Jean Heller, who told her colleague, “There might be something here.”

Heller’s story was published on July 25, 1972, and led to congressional hearings, a class-action lawsuit, and a lawsuit seeking $10 million in damages. settlement The study was completed about four months later. In 1997, President Bill Clinton formally Apologized He criticised the study as “shameful”.

The leader of a group dedicated to the memory of the study participants said Monday that he was grateful to Buxton for exposing the experiment.

“We’re grateful for his honesty and courage,” said Leel Tyson Head, whose father was involved in the study.

Buxton was born in Prague in 1937. His father was Jewish, and his family emigrated to the United States from Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia in 1939, eventually settling in Irish Bend on the Columbia River in Oregon.

In his complaint to federal health officials, he compared the Tuskegee study to medical experiments conducted by Nazi doctors on Jewish and other prisoners. Although federal scientists did not believe they were committing similar moral or ethical crimes, after the Tuskegee study was exposed, The government introduced new rules There is an ongoing debate about how medical research should be conducted, and today, this research is often blamed for some African-Americans being unwilling to participate in medical research.

“Peter’s life experiences quickly determined that this research was morally indefensible and he sought justice in the form of treatment for these men. Ultimately, he couldn’t give up,” the CDC’s Pestorius said.

Buxton attended the University of Oregon, served in the U.S. Army as a combat medic and psychiatric social worker, and joined the Federal Health Service in 1965.

Buxton continued to write and speak, and was awarded a prize for his involvement in the Tuskegee Study. He traveled the world and collected and sold antiques from the California Gold Rush, including military weapons, swords and gambling equipment.

He also spent more than 20 years trying, with partial success, to recover his family’s property that had been confiscated by the Nazis.

“Peter was smart, witty, elegant and always generous,” said David M. Golden, Buxton’s best friend for more than 25 years. “He was a strong advocate of individual freedom and frequently spoke out against prohibition, including drugs, prostitution and firearms.”

Another longtime friend, Angie Bailey, said she has attended many of Buxton’s presentations about Tuskegee.

“Peter never finished a story without fighting back tears,” she says.

Buxton himself has played down his actions, saying he did not expect the strong reaction from some health officials when he began to question the ethics of the research.

At a forum at Johns Hopkins University in 2018, Buxton was asked where he got the moral strength to blow the whistle.

“It wasn’t strength,” he said. “It was stupidity.”